Part One: Types of Teams

Written to sort out my thoughts for my UXDC keynote. If you’d like me to speak at your conference on high performing teams, check out cwodtke.com

“High Performing Team” is the holy grail for modern companies. Everything we make is not only interactive, “smart” and connected, but then has to be polished, packaged and promoted. Apparently it not only takes a village to raise a child but also to ship a toothbrush. We have to learn to work with other people to be successful.

Teamwork is tricky. Sartre said, “Hell is other people.” If you’ve been on a bad team, you know what he means. In my ~30 year career in tech, I’ve played many roles on a team, from worker bee to leader to overseer. In that time, I’ve been haunted by the mystery of why things go so very wrong so very often.

Trying to solve this mystery, I’ve read a gazillion writings on teams, including the obvious: Wisdoms of Teams, Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Teaming, Committed Teams, and David Bradford’s writings. I’ve lost many hours on JSTOR (I think I may have a problem.) I’ve run experiments with my students and further refined emergent practices my clients. I finally have a model that helps teams succeed.

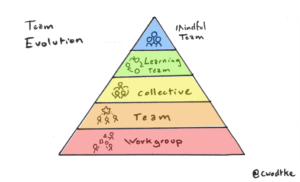

The big insights:

- There many kinds of teams, and you should decide what kind you need first.

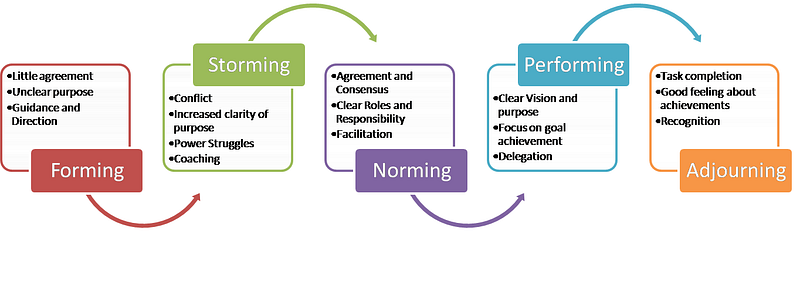

- Teams have stages, but it’s not linear. It’s iterative. Great teams are willing to storm, norm, perform, then storm again and re-norm in order to constantly grow.

- Teams need to consciously co-design the core three key elements of a team— goals, roles and norms — to be successful.

In this ridiculously long article, I’ll unpack all three ideas (and yes, this wants to be a book. I’m on it. Sign up to be notified when it’s available.) Part One is on types of teams, Part Two is how to build high functioning ones.

I want feedback on this article, so feel free to respond! (i.e. is a collective team actually distinct from a learning team?)

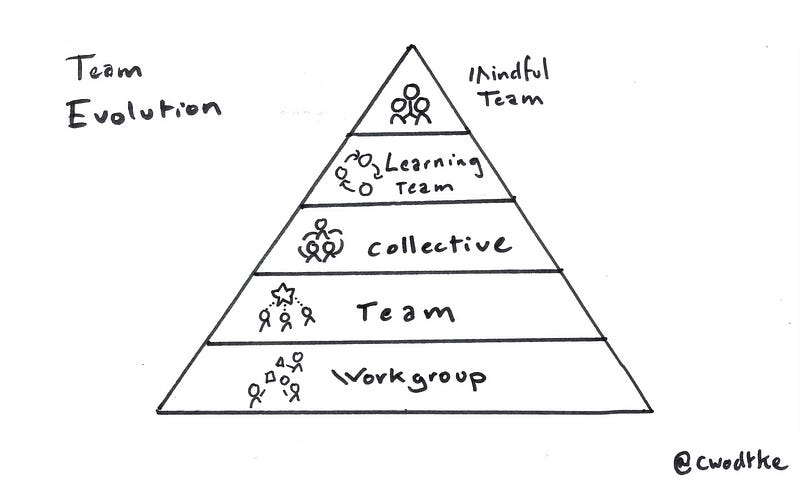

Types of Teams

Workgroups

You don’t always need a “team.” Sometimes you just need skilled bodies.

You don’t always need a “team.” Sometimes you just need skilled bodies.

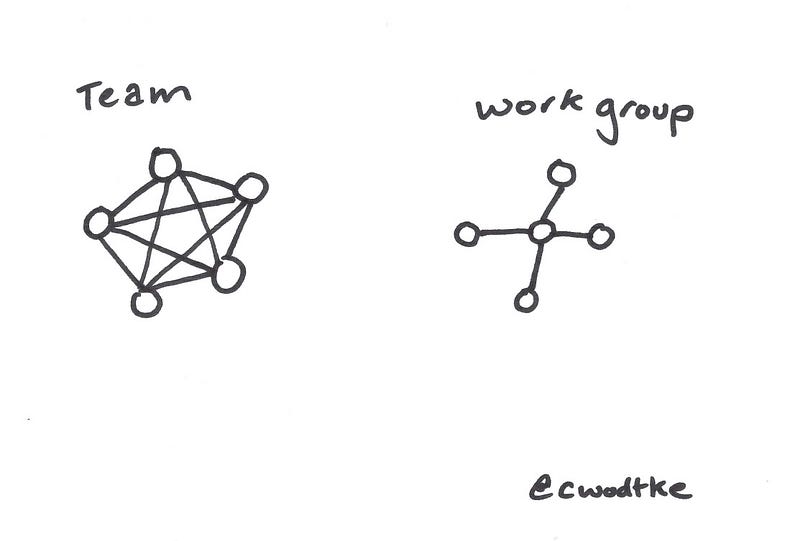

The workgroup is a proto-team. It’s a group of individuals working separately, coordinated by a boss. A customer service “team” or a group of salespeople are good examples of workgroups.

David Bradford writes

“Groups are most appropriate when the greatest benefit comes from members maximizing their individual efforts with each person achieving his/her sub-area goals. Meetings are spent supporting such individual performance (and giving the leader the information to integrate the separate parts). Such sessions are highly structured with an emphasis on transmitting information and making decisions (but less on joint problem-solving). With a group, the whole is the sum of the parts and the objective is to make sure each part is successful and coordinated with the others.”

Teams

A Team is the evolution of the workgroup. You need a team when you need a multi-disciplinary group to act in a coordinated manner over time toward a shared goal.

A Team is the evolution of the workgroup. You need a team when you need a multi-disciplinary group to act in a coordinated manner over time toward a shared goal.

In The Discipline of Teams, Katzenbach and Smith wrote “teams have four elements — common commitment and purpose, performance goals, complementary skills, and mutual accountability.”

These first two properties can be addressed with OKRs, which I’ve written about extensively.

The third — complementary skills— is a prerequisite for any sort of maker team. For example, in many game design companies, a new game will start with a micro-team of a game designer, a business person (producer or product manager,) an engineer and an artist.

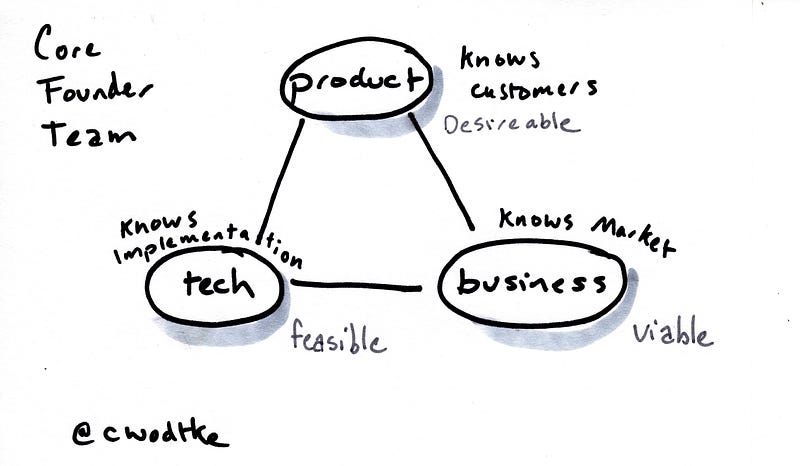

I remember back when I was first pitching my startup around, and an angel investor drew a triangle on his whiteboard. He said for a startup to succeed, it needed people with skills in product, business and tech.

He said it didn’t have to be three people each with one of the skills, but all three skills had to be there. It’s good to remember that people are usually more skilled than their role requires, and there is more an one way to design a team.

In a nascent team, the fourth requirement — mutual accountability — most often manifests as people demanding everyone “pull their own weight.” In a healthy team, the engineer will walk over to the designer and ask for a missing design component. In a dysfunctional team, he’ll ask the PM to dealwith the designer, sliding backward towards workgroup behavior.

Collectives

In what I’m calling a collective, you see shared decision making and shared responsibility for goals. All members have a clear vision for what they want their results to be, and they both help each other and hold each other responsible.

In what I’m calling a collective, you see shared decision making and shared responsibility for goals. All members have a clear vision for what they want their results to be, and they both help each other and hold each other responsible.

This is the high functioning team that has reached the “performing” stage.

Bruce Tuckman wrote in ‘Developmental sequence in small groups’ that groups moved through various stages to become functional groups.

The collective is what you need if you have a temporary group of individuals to work together toward a shared goal without much to any oversight. If the team is permanent, consider making it a learning team.

Learning Teams

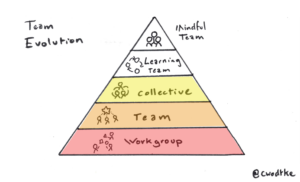

In a learning team, not only is the team performing as a unit, but they are also working together to become better every day. The question each new status quo, and make hypothesis about how they can be more effective. I believe in this type of team the stages look more like this.

In a learning team, not only is the team performing as a unit, but they are also working together to become better every day. The question each new status quo, and make hypothesis about how they can be more effective. I believe in this type of team the stages look more like this.

A learning team (or maybe I should call it a lean team, as it closely resembles the continuous improvement of lean manufacturing and the learning cycle of lean startup) shares a commitment to progress.Knowledge is shared out as soon as it’s acquired, and the team is continually developing new hypothesis to be tested.

A critical component to this team’s success is a tolerance forcreative conflict. Many teams are willing to put up with the storming that comes when you put people together who don’t know each other. It’s expected we’ll fight, misunderstand each other, disagree on goals and outcomes. And it’s a relief when it settles.

But it’s a rare team that is willing to re-enter the land of conflict after it’s figured out how to work well together. You’ve heard that you must break a leg again if it’s set wrong? It’s the same situation when a team has settled into bad (or even so-so) patterns. A great team must step back into conflict again and again to break the substandard status quo and find the best way to execute.

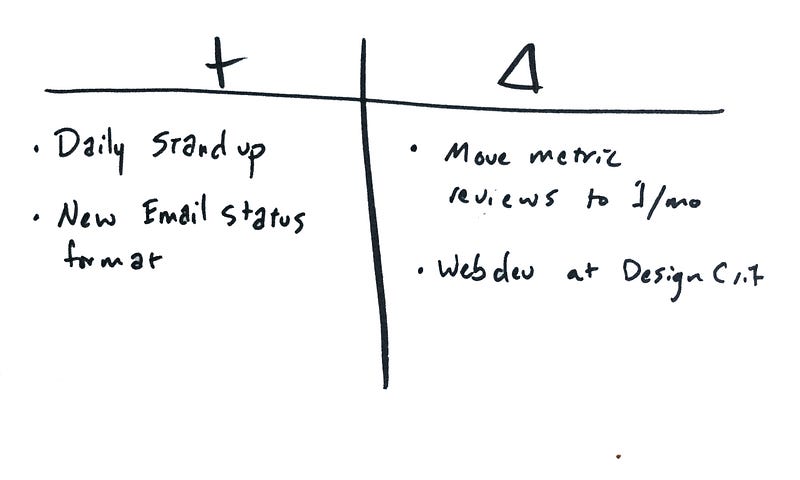

Postmortems, in which a team gathers together to examine what worked and what didn’t, can be powerful or an exercise in passive aggressiveness. A learning team creates a rhythm of introspection and evaluation. Some do it at the end of each project, some will make a simple “keeps” and “changes” tally each week. What matters is the learning cycle. (I recommend both, btw)

The Mindful Team

My final team type is the Mindful Team. It’s a joke that there is no “I” in team. But what if putting the I back in team was important? The mindful team not only takes care of the team’s growth and learning, but in each individual’s. They care about each other as people as well as colleagues. I thought about calling this the Soylent Team, as a reminder that teams are made of people.

My final team type is the Mindful Team. It’s a joke that there is no “I” in team. But what if putting the I back in team was important? The mindful team not only takes care of the team’s growth and learning, but in each individual’s. They care about each other as people as well as colleagues. I thought about calling this the Soylent Team, as a reminder that teams are made of people.

The mindful team is needed to make a holacracy work (if you are into such things) because each team member manages and grows the other. In a more traditional company, the mindful team can make up for departments with too many direct reports, unskilled managers and and even dysfunctional executive leadership. A mindful team is not mandated, it is chosen by the team. In that lies its power.