In one of the classes I teach at CCA, students were confused by mental models, conceptual models, concept maps, etc. I ended up drawing a taxonomy for models on the whiteboard, and it may help others. This post is for them first, then you!

Admittedly, there is no worldwide agreement on these terms, because humans make things and name them as they see fit, often without searching for previous work. UX Design (a.k.a. product design a.k.a. interaction design a.k.a. information architecture etc etc) has a tendency to name and rename things. Ambiguity is inevitable.

I live in hope of a controlled vocabulary for digital design.

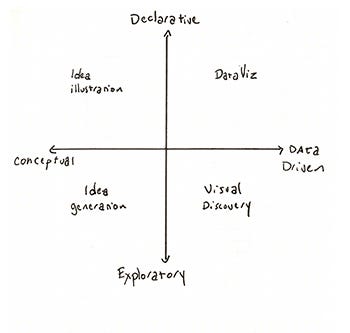

Let’s start with this model of models by Scott Berinato, author of Good Charts. The five models we are about to explore are exploratory/conceptual or exploratory/declarative models (or maps or diagrams.) That means they are based in IDEAS not DATA. In theory a MAP should document existing territory, and a MODEL proscribe a new one. But hey, see above.

These five diagrams are particularly useful for understanding complex systems. This seems more important every day, as we are all complexifying things full time.

This post will cover

- Mind Maps, to gather your thoughts

- Concept Maps, to organize your understanding

- System Maps, to map the system (a tautology, but an accurate one)

- Mental Models, to understand and communicate your user’s understanding

- Concept models, to message a way to think about a complex system

The first two diagrams are exploratory, i.e. for ordering your thinking. You can do this alone, or with your team. Of course, once you’ve explored, you can tidy them up and make them explanatory.

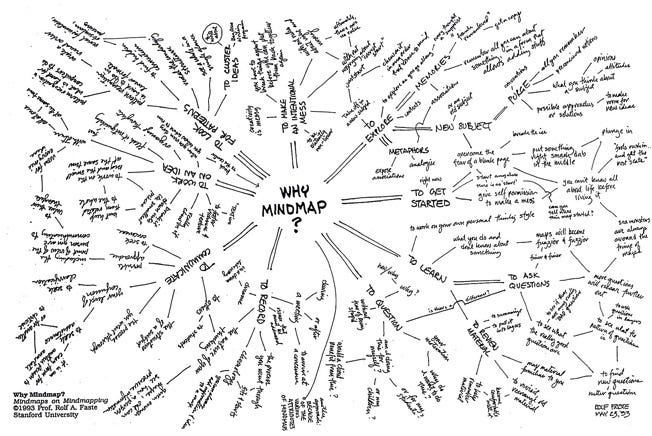

Mind maps

This is a great way to dump all the stuff in your head onto a piece of paper so you can see it all and make connections. You can move from related items to emotions to ideas.

You can use it to diagram contexts, take notes of readings, or just wander from concept to concept in your head. You can make them on a whiteboard with a team to create a shared vision of the world. You can scribble them in a notebook to brainstorm. You can ask a potential user of your product make one, so you can understand their understanding more effectively (which is useful later, when we make mental models.)

Because Mind Maps are easy and have few rules about how to make them, they are a great way to begin modeling a system.

From Rolf Faste’s MindMapping article

The basic principles of mind mapping are:

1 Create a Center Statement.

2 Develop ideas radially outward.

3 Capture ideas quickly.

4 Use lines to show connections.

5 Create train-of-thought structures.

6 Follow an idea as far as it will go.

7 Work from the known to the unknown.

8 Return to the center when ideas are exhausted.

9 Increase density to create richness.

10 Avoid being judgmental.

11 Have fun with the form.

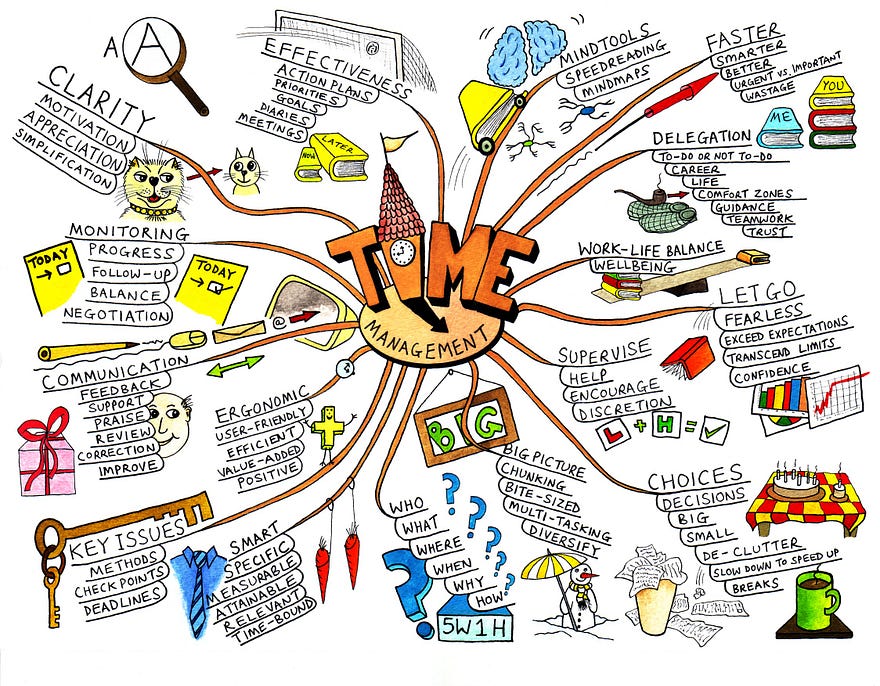

Even though MindMaps started as a simple way to get the stuff in your head out where you can see it, some people make them fancy…

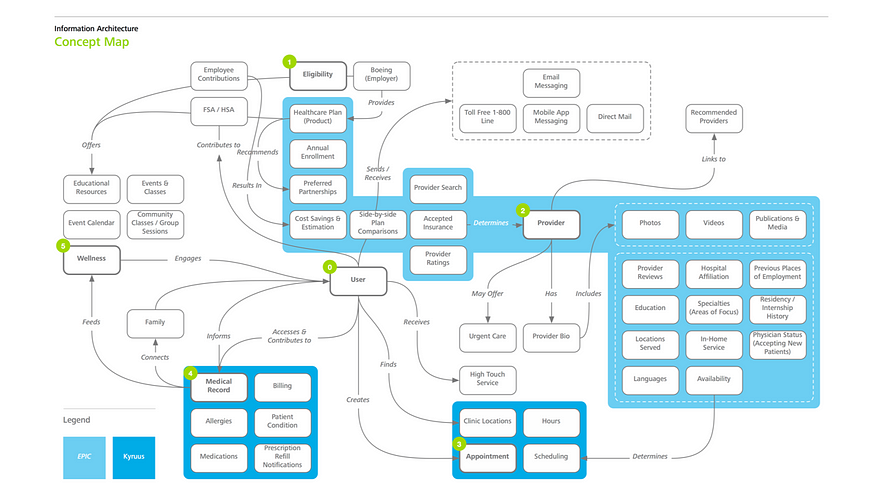

Concept Maps

Concept Maps are a bit more formal than a Mind Map. In a concept map you name the relationships between the items. Hugh Dubberly pioneered their use to understand complex systems, but many folks have since adopted them and they should be a standard part of your toolkit. Dan Brown explains them thusly (we’ll pointedly ignore him calling them concept models for now.)

In Hugh Dubberly’s article, Creating Concept Maps, he lists these steps for creating them.

List terms

Edit the list

Define the remaining terms

Create a matrix showing the relations of terms

Rank the terms

Decide on main branches or write framing sentencesFill in the rest of the structure

Revise

Apply typography to reinforce structure

Revise

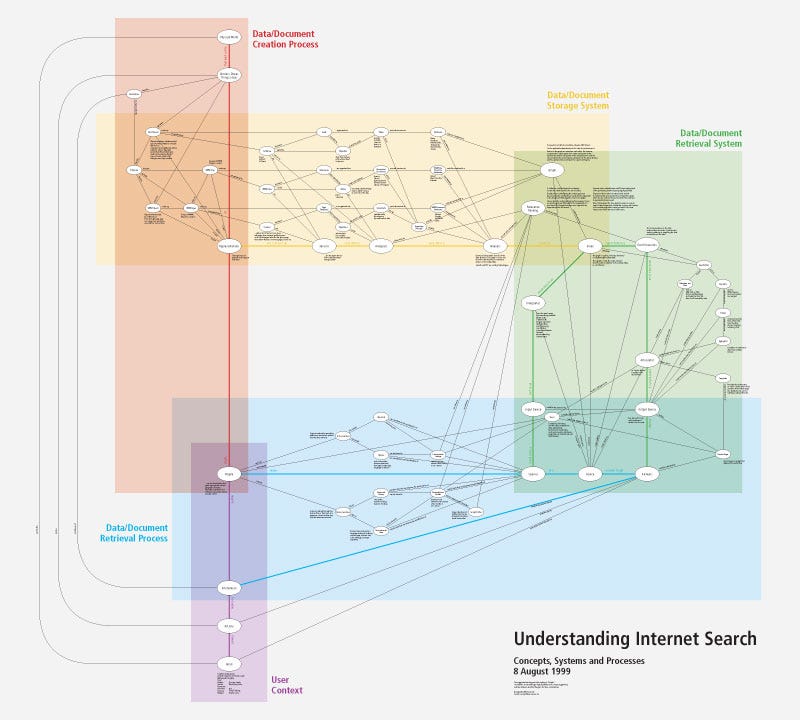

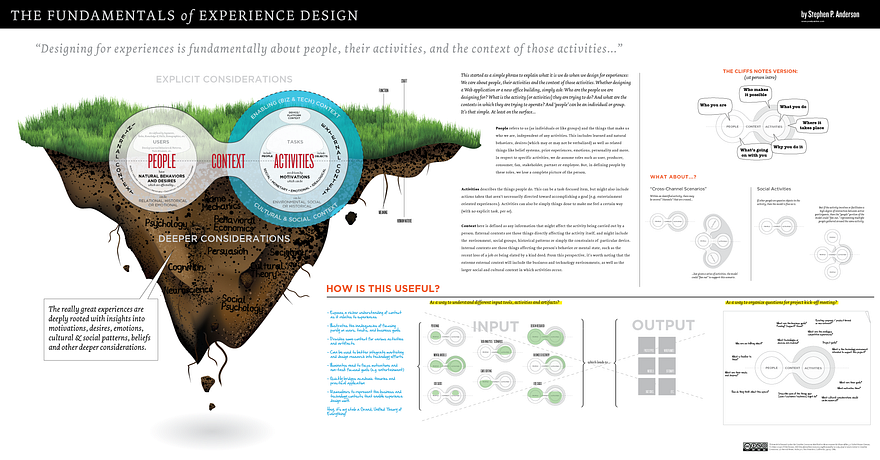

Concept Maps can be simple, if it’s just for your own use in your design process, or they can get fancy if you want to make a poster for a client or your team. Posters are great for keeping a shared vision and inspiring conversation.

Concept Maps can be a powerful tool for helping a team understand the space they are designing in. I had this model of Search on my cubicle wall at Yahoo in 2002, and the engineers and I would use it to discuss innovations and ferret out issues.

The next three models are mostly explanatory, i.e. about messaging understanding for internal teams or for your customers and users. Of course, first you have to understand, then you can explain.

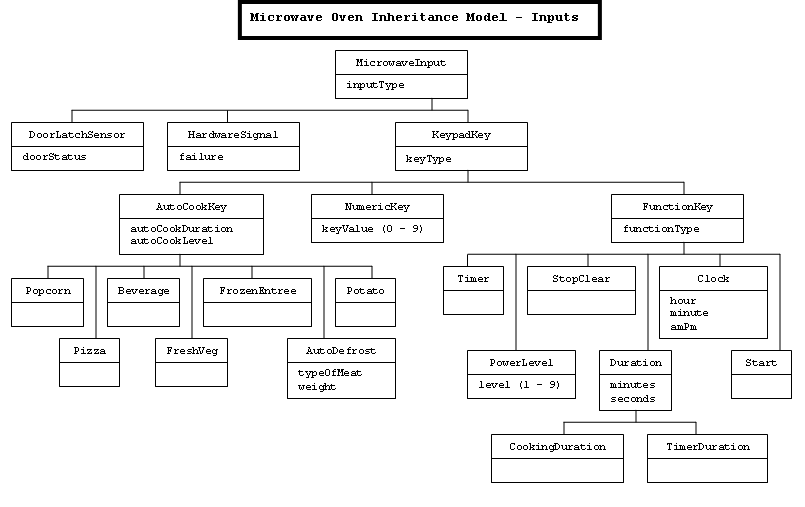

System Models

A system model’s job is to document a system as accurately as possible.

They can be overwhelming if you aren’t familiar with the system. Making one can help you become an expert in understanding the system. System models are great as posters for the same reason as concept maps: to keep a shared understanding of the system where the entire team can see it. I can’t tell you how many times an engineer has walked past a system model and said, that’s not right. As the system changes, team members can update with is a marker. On the wall means it lives in a state of permanent critique.

System diagrams can encompass content or behavior. They can map existing system, or document ones to be built.

When I was working at Blizzard I was making UI flow diagrams and I noticed that a few engineers were hanging the documents on their walls for reference.

-Stone Librande

The danger of system models is that once you know the system, you forget how confusing and complex it is. That’s when you need a mental model.

Mental Models

This is a model of how the end user thinks about a complicated system. Users will ignore the complicated irrelevant parts of a system and attend what they care about. They are often inaccurate, incomplete and editorial.

You draw mental models to help your team (and yourself) understand how the potential user of a system currently thinks about the system.

This is my favorite example ever.

Indi Young took the mental model concept, used a end-user’s task as an organizing principle, applied research using a gazillion interviews because she is THAT GOOD, and came up with a way to map your offerings (or your competitors) to it. It’s the love child of mental models and gap analysis, and it’s a powerful tool. You should buy and read her book, Mental Models.

If I was naming it, I would have called in the mental model/offering analysis, but it is too late now. The cat is out of the bag.

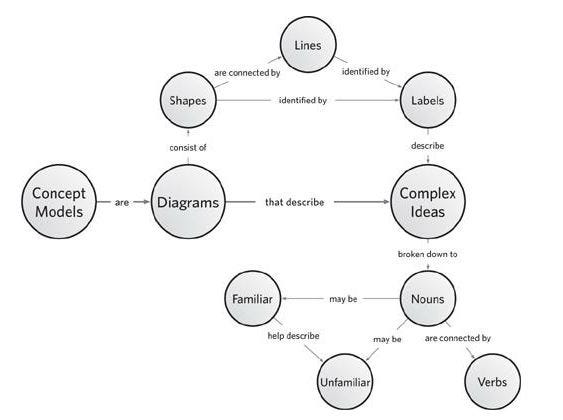

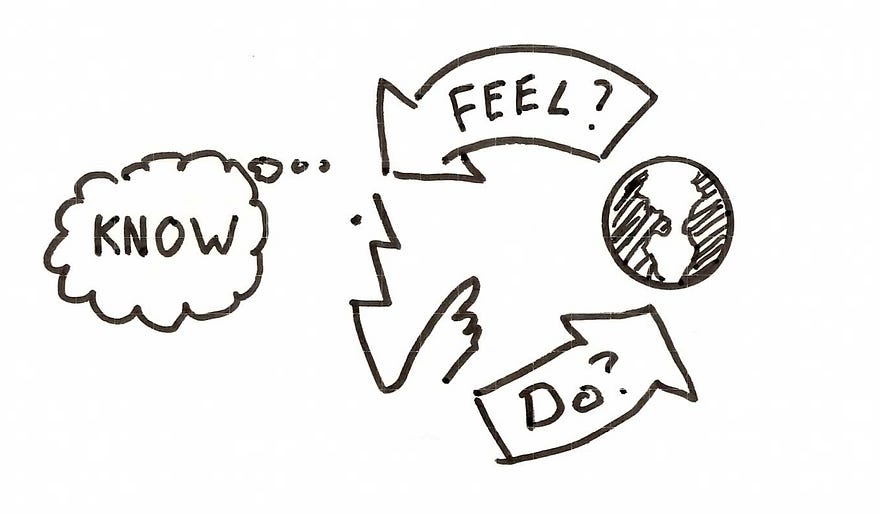

Concept Models

“A conceptual model is an explanation, usually highly simplified, of how something works. It doesn’t have to be complete or even accurate as long as it is useful.”

― from “The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition”

A Concept Model is how you WANT people to think of the system. You don’t want to include every little thing as in the system model, but you also want ot avoid users making stuff up as they do in the mental model. A concept model is first and foremost a message.

I’ve seen the concept model used several ways.

One is to tell your end user how to think about the system. Or more likely, the value of the system.

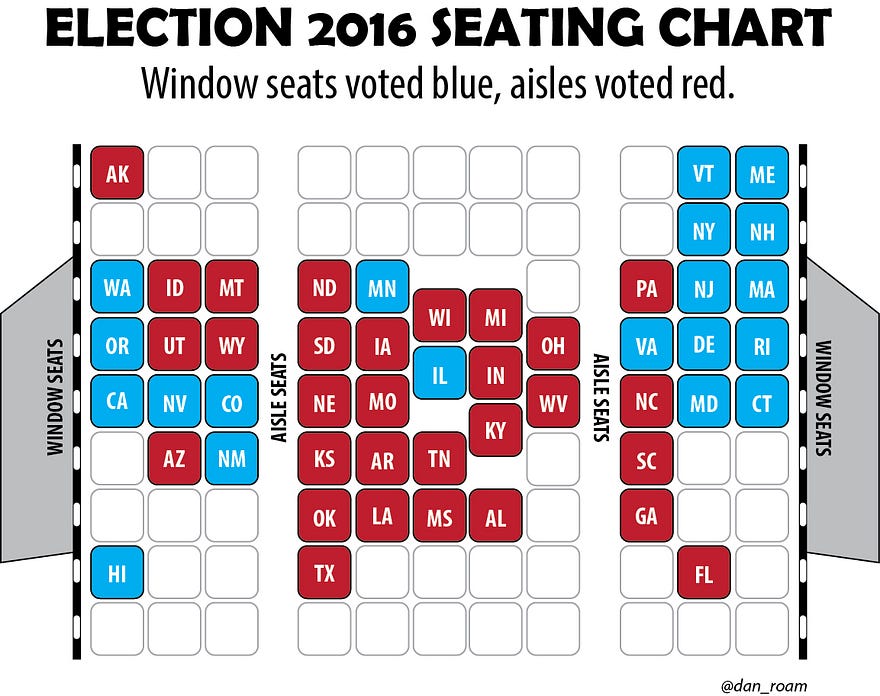

Dan Roam, author of Back of the Napkin, draws concept models to explain the world. The world is a messy complex system.

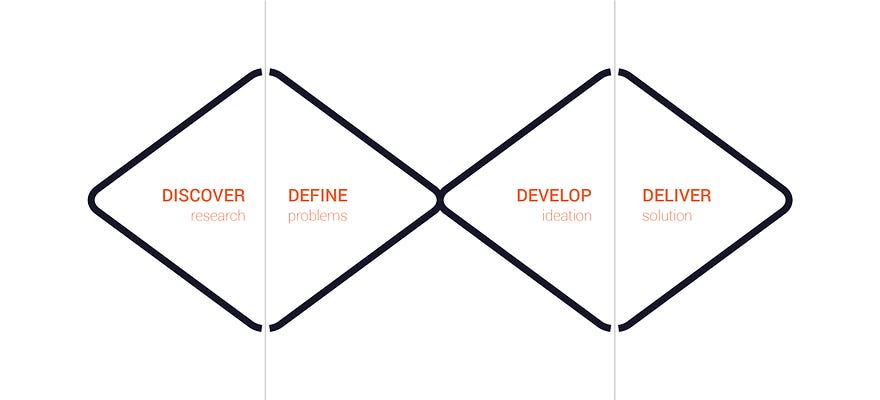

You can also use Concept Models to explain processes

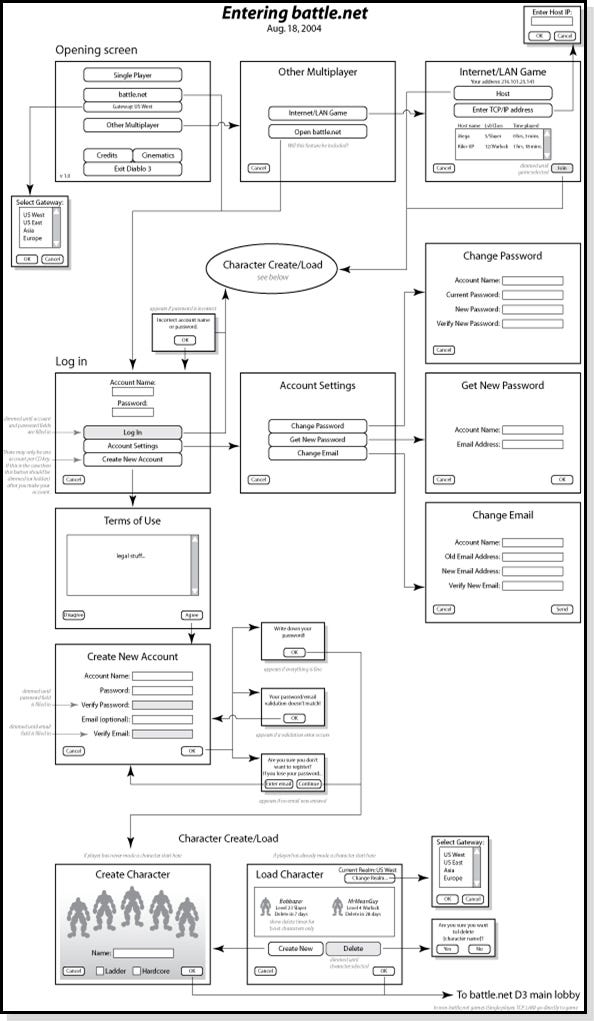

For The Team

You can use concept models inside your company, to communicate to your team members how to visualize the system your are designing.

A long time ago, we used site maps to explain to the team what we were designing. Site Maps are essentially System Diagrams. But sites got really big. Thousands of pages. Hard to show in a diagram.

Most designers moved from making system models (complete) to making concept models (core ideas) to message the key organizing principles.

Stone Librande’s One Page Designs are concept models of game design decisions. He makes posters for his team to create shared understanding.

From his talk on One Page Designs

Here is a simple template to use.

1)What is the title of your document? If you don’t know then ask yourself why you are making it.

2) Make sure to date everything. Since these will be printed out and passed around the office it is the only way to keep some sort of version control.

3) Give your diagram a lot of whitespace. If you cram things too close together than no one will want to take the effort to read it.

4) A central illustration in the middle of the diagram can help draw attention and acts as a focal point.

5) Under the central illustration put a description with additional explanation text.

6) Use callouts around the illustration to give extra detail.

7) Some of your callouts may be illustrations, too. Add notes underneath to clarify important concepts.

8) Use sidebars and bullet points as checklists, high-level goals, or other necessary information.

Pay attention to the size of things. Make important things bigger. This includes font sizes as well as illustrations.

Start out at letter size, then work up to legal, 11 x 17, and posters as the need arises.

Concept Models can be super sexy

Or simple things you draw on the whiteboard

Learn How to Make a Concept Model in this article I wrote for Boxes and Arrows.

I also should point out I’ve been chided by some of my peers for not calling them conceptual models. Tough luck guys! Concept Model is shorter to type!

Model, Maps, Canvases…

There are many more models and maps out there, and a new category of interactive models, canvases. The five models I have covered in this article are just a handful of sensemaking tools we can use.

For now, young designer, start with

- Mind Maps to gather your thoughts

- Concept Maps to organize your understanding

- System Maps, to map the system

- Mental Models to understand and communicate your user’s understanding

- Concept model to message a new way to think about a complex system

Go draw, and make this wacky world make sense!

See also: Models, Maps and Canvases by Dave Gray