“Perhaps because polish is so visible, many people erroneously believe it to be the most important part of writing. But polish is merely the plaster on the walls of structure.

The proof is in the window of the bookstore down the block. The display of current best sellers no doubt contains several titles by tin-eared pop novelists who wouldn’t recognize a graceful sentence if it asked them to dance. The likes of Jean Auel and Tom Clancy sell books by the millions because they understand story structure, a point that’s lost on the critics who savage their syntax.” –Jon Franklin

Just after college, I decided to get my masters in creative writing. I loved (and still love) books more than just about anything. And I loved graduate school: reading, writing, even critique.

But when I came to do my thesis, I decided to write a novel and I stalled. I got mired down in the “second act” and never recovered. To be honest, I was boring myself. I just wasn’t interested in what my characters were trying to do.

It would be ten years before I’d learn what went wrong.

There is only one basic shape to a story, all else is variations

Do you want people to listen to your presentations? Do you want to convince people to change for the better? Do you want to write compelling stories? I sure do. So I did the research.

I’ve spent the last two years studying story architecture, reading everything I can get my hands on. I’ve read books by genre authors who write sci-fi, romance and horror. I’ve read literary greats, journalists, movie scriptwriters and comic book authors. Campbell? Freytag? Check and check. Three acts, seven points, circle, diamond and arc, I’ve got them. But for me, the biggest OMG was when I watched Kendall Haven’s video on the science behind story. You see he’s a scientist and storyteller who got a DARPA grant to study the body’s reaction to story. He did it all: MRI’s, electrodes, dopamine swabs. And his eight elements that create engagement mapped to the wisdom of the best-selling authors.

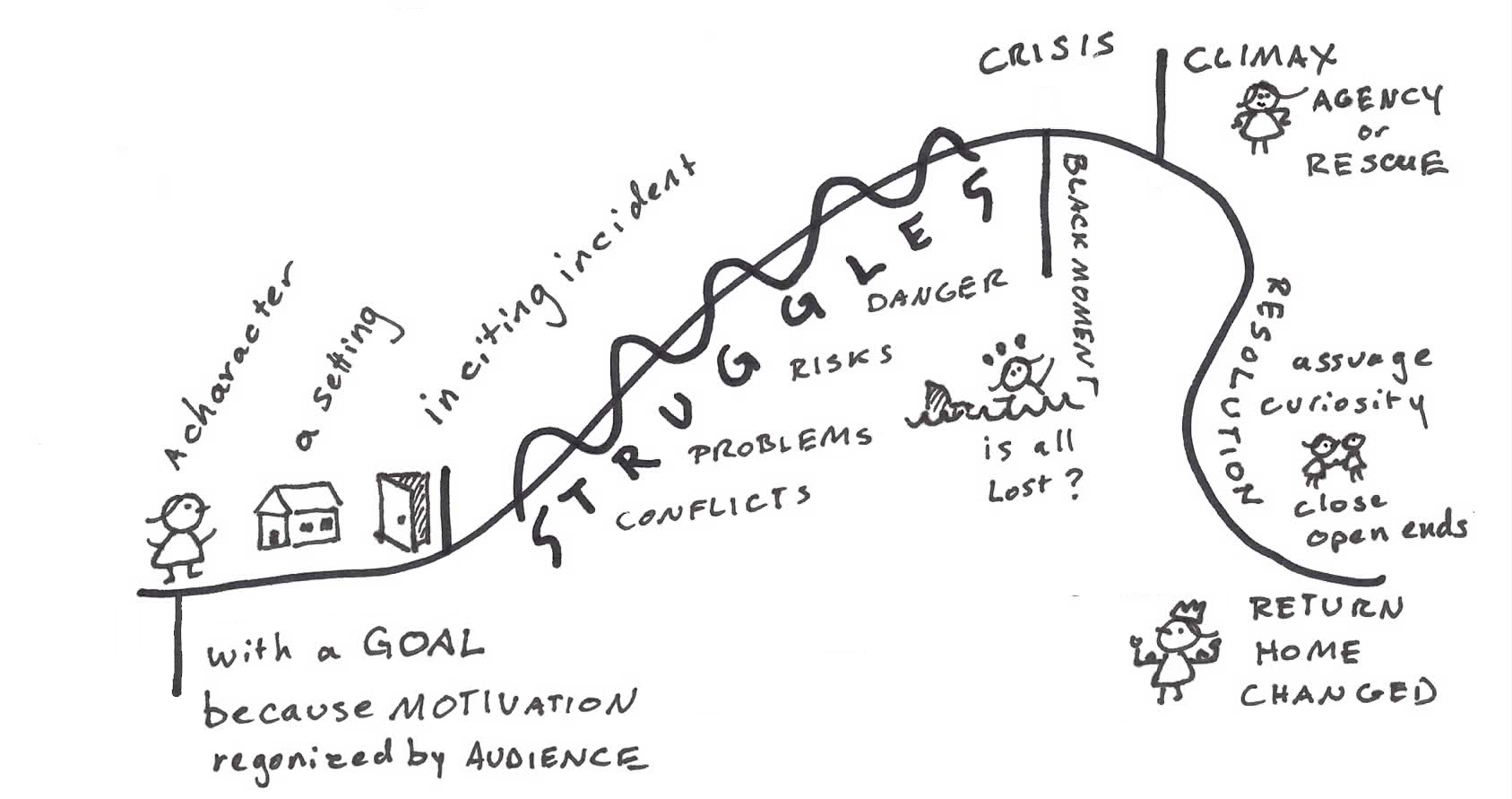

This is how I boil it down.

1. Start with Conflicted Characters

Get it wrong, and the entire story falls apart. The character needs a goal, a motivation and a conflict (GMC). The goal can be alien to your audience, but the motivation must be shared by them, and the conflict creates struggles that increase engagement.

Harry Potter (Sorcerer’s Stone): Wants to stop an evil wizard (like you do) because he wants to protect his new-found home (universal motivation!) but he’s regarded as a kid and people don’t take him seriously (external conflict).

Mad Max (Fury Road): Want to help wives escape (whatever) to get redemption (don’t we all want forgiveness?) but has a bad case of nihilism AND heroism (inner conflict). Also, a whole lot of Warboys not afraid to die to stop him (external conflict)

Dorothy Gale (Wizard of Oz): Wants to go home (really? She is choosing Kansas over Oz?) to be with people she loves (that, I get) but Oz is a tricky place to navigate (external conflict). As well, though it’s cloaked in the metaphor of the ruby slippers, she has to learn to trust her own abilities (internal).

When the conflict is external, it’s mostly a function of plot to provide interest. Interest heightens when you include both internal and external conflicts. A great character is at war with herself as well as the world, and a satisfying arc with when she can overcome both by her own agency. Harry is a bit of a boring Mary Sue in the first book/movie, but becomes steadily more engaging as he starts to deny his chosen status, struggle with confidence and grows distrustful in authorities. His refusal to trust Snape and his growing fascination with Voldemort makes The Order of the Phoenix one of the more interesting movies (though I think the book is weaker, as Harry becomes tiresome with his endless teen moping.)

2. Paint a picture.

You know that magical feeling when the world disappears and you are having a story playing in your head? Even though there were no literal pictures, as in The Night Circus or Swimming to Cambodia, you’d swear you saw the story happen? Details transport you into the story.

“All over the tents, small lights begin to flicker, as though the entirety of the circus is covered in particularly bright fireflies. The waiting crowd quiets as it watches this display of illumination. Someone near you gasps. A small child claps his hands with glee at the sight.” Erin Morgenstern, The Night Circus

But it’s not just for setting! Characters need traits to bring them to life. An accent, a physical anomaly or a quirk paints a picture of a rich and storied past. Screenwriter Blake Snyder calls this “A limp and an eyepatch” — they are details that stand in for a backstory. Nick Fury in Avengers is a great example. His eyepatch covers a scarred eye that tells us he’s see real action.

But be careful! Too many details and the story gets bogged down:

“exposition is the enemy of narrative. Good exposition provides just enough backstory to explain how the protagonist happens to be in a particular place, at a particular time, with the wants that will lead to the next phase of the story. Thorough reporting produces overwhelming detail. Good storytellers cut through it to create a clear path leading forward.”

― Jack R. Hart, Storycraft: The Complete Guide to Writing Narrative Nonfiction

3. Make the protagonist suffer.

We have been telling stories for over 300,000 years. Before we invented writing, we used stories to share hard-earned knowledge: don’t eat the red berries with the spots. Don’t pet the big kitty. Our brains have evolved to pay attention to story, because they hold secrets to our survival. The stories that matter most are the ones in which the problems are the hardest.

If you want your audience to sit spellbound through your story, you need conflict. Three of Haven’s eight elements are about that: Conflicts & Problems, Risks & Dangers and Struggles. Many new writers grow fond of their characters and have a hard time putting them hell. That’s a mistake.

“Be a Sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them-in order that the reader may see what they are made of.” Kurt Vonnegut, How to Write a Great Story

Progression is critical. Things must get steadily harder, and as your protagonist grows more competent, the challenges get worse. This keeps the brain riveted.

4. And when it can’t get any worse, make it worse before it gets better.

The two key moments that create the peak of excitement in a story is the darkness before the dawn, and the dawn. I’ve seen these referred to as the black moment and the realization, and the crises and climax. Jim Butcher, author of the Dresden files, often will have an early crises where you are convinced things cannot get any worse. Then, he finds a way to make things worse. His books keep me up past midnight every time I read them.

The climax is the moment when the protagonist is either rescued or rescues herself. In Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet, it’s the entrance into act three when the characters get an idea on how to resolve the core struggle. In older tales, we saw a lot of Deux ex Machina– the hand of god– rescuing the hero. A hero could be rescued by luck, a partner, another hero… but modern audiences strongly prefer stories where the protagonist helps herself.

5. Resolution is boring, keep it short.

There is a simple reason I draw my arc in the shape of a wave. Interest grows with every additional conflict, but once the hero figures out the solution, our fascination collapses. Don’t natter on while the audience’s mind is drifting.

A resolution can be too short, like most Jane Austin novels where the hero goes from “I love you” to married in two pages. A resolution can be too long, as in Return of the King where I counted about five endings last viewing. We do want to know how it all turns out, we do want loose ends tied up. But like exposition, keep resolution short and vivid.

The secret of the three act structure is they are not of equal lengths. Act one tells you how the world is. Act two turns it upside down. Act Three has the protagonist make it make sense again. But Act two is the good part. It has the struggles, the set back, betray, heartbreak… everything we love.

Also Consider

You need a good inciting incident to move your protagonist to action. Bilbo longed for something more, but didn’t know what until Galdalf carved a sign on his door inviting dwarves to dinner.

A setting is more than a place, it’s a situation and a moment in time. A vivid place has details. Annie is a poor orphan living in cruelly run orphanage in the depression when few would-be parents can afford another mouth to feed.

Modern audiences prefer “return home changed” to “return home the same.” Our modern life has more jerks than tigers, so we hope for a story where the main character learns something. (Hopefully how to stop being such a jerk.)

You can use these tools any time you are worried people don’t care. I used it in when I choose the format of these articles:

How to Make a Concept Model

Towards a New Information Architecture

In both cases, the subject was one I cared about, but more people think is dull or obscure. These have both been some of my highest clicked writing ever.

I didn’t bother in this short essay because Story is already an interesting topic to many, and I wrote this mostly for story nerds like myself!

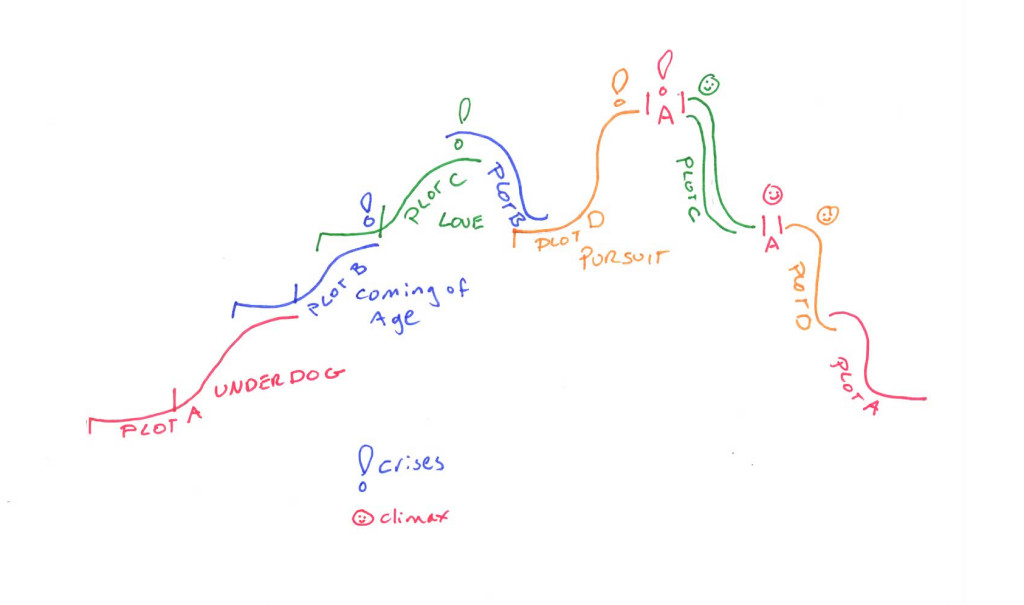

So what about Plot and Genre?

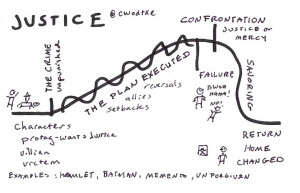

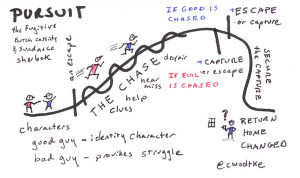

Plot is What Happens Along the Arc

You can argue my arc is the ur-plot. I believe that plot is actually the events and types of characters you put on the curve. There are a ton of archetypal plots (Five? Seven? Ten? Twenty?). Let’s look at a few.

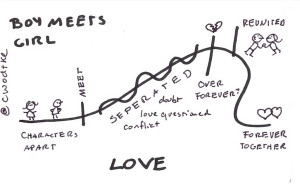

Boy Meets Girl.

You can one main character and a secondary, or you can flip back and forth between the two. Internal conflict is always satisfactory (she believes love interferes with his career, he believes love interferes with his beer.) The crises usually revolves around betrayal– lying, cheating — and the climax shows it was a misunderstanding or we get atonement.

The struggle is always about them being separated. The resolution is about binding them more tightly together than ever.

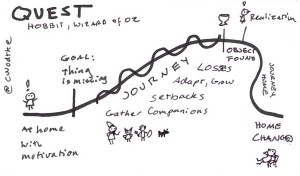

The Quest

Hellooo monomyth!

You seek a things, and find yourself. Return home changed and don’t pass go.

Common elements include companions, a mentor, great losses and extreme character arcs. I’m pretty sure Ocean’s Eleven is actually a quest story. Ocean’s Eleven and Lord of the Rings have remarkable similar structures. Which means Quest and Heist are closely related if not the same.

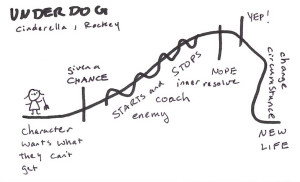

The Underdog

Even though they do not have a shot in hell, the underdog wants something. They want it so bad. From Cinderella to Rocky, the underdog represents our own hidden hopes and dreams. The struggle tends to involve “they got it!” “No they don’t” “Ok, now they got it!” “Or not so much.”

Common elements include an enemy who blocks their path, and a coach who helps them forward.

In this case, they do not return home changed but rather move into a new life that fits their changed self.

Coming of Age

Naive person has the world teaches them a hard lesson, and they become a better person for it. Stand by Me, Catcher In the Rye, The Devil Wears Prada.

Struggle revolve around life sucking and then sucking more. The hero grows and becomes better because of it, and via new understandings becomes competent. In some tragedies, the world breaks them.

They can return home changed, but more often they move to a new life they have earned.

Genre is a collection of tropes that tell you what the plot elements look like. Trope is defined by the amazing TV Tropes as “a storytelling shorthand for a concept that the audience will recognize and understand instantly.” Because they are used so often, an author can quickly paint a picture with only a few words. For example, in Steampunk, the heroine is often described as not wearing her corset/petticoats and sneaking off to tinker. We now know she will fight against societies expectations to find fulfillment and happiness. She likely plucky and resourceful, and a forbidden love is probably not far behind. Most readers take pleasure in the use and the breaking of the trope equally, as it follows the recognize/surprise rhythm of story shape.

Formulaic?

Some people may find the arc constraining, but I find it freeing. So much great literature and super awesome TED talks follow this shape precisely, and thousands of unique stories have been told. Being interesting is more useful than being unique.

As well you can weave them together to make subplots in further increase tension.

Multiple plots woven together makes the whole story not only unique but very compelling.

Please, Can I Have Some More?

I’ll be continuing to document plots against the curve, and will publish on twitter as I go along.

I did a quick video of my thinking on story structure for some friends on twitter, because let’s be honest, explaining anything with 140 characters is a nightmare.

And if you really want help shaping a story for a pitch, a presentation or another format, ping me on Clarity! I can provide story workshops and/or individual coaching on using story in your presentations and pitches. If you want to use Story in product design, check out my pal Donna Lichaw’s work!

I love good story, and hope you use this information to make better ones in your presentations, reports and even… gasp… in that novel you’ve been meaning to write!

Here is how I use it when creating a presentation: Secret to a Great Presentation

Here is how I run an improv from it!

Addendum: This article on Kishōtenketsu suggest there might be another shape that uses (IMO) mystery rather than conflict ats the driving force of the shape. It’s well worth considering as an alternative/expansion.