This is Part 2 of a three part series on high performing teams. Part one is of Design the Team You Need to Succeed

Now you’ve decided you want more than a workgroup, what should you do? What does it take to make a high performing team? Where to start?

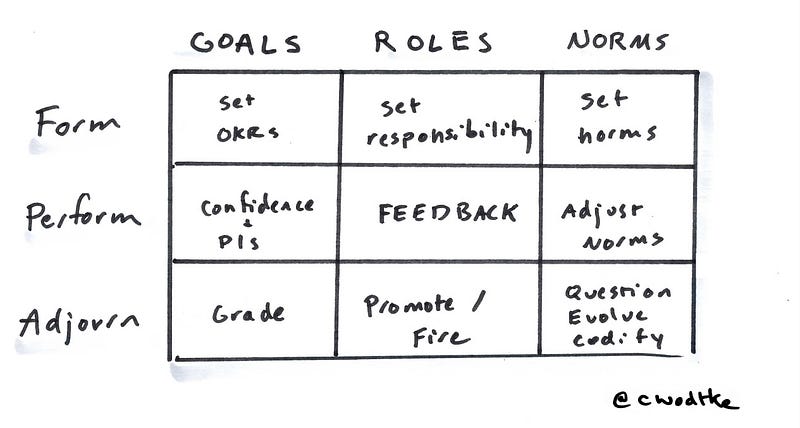

Research on group dynamics shows that teams perform best when they agree on rules related to goals, roles, and norms

— Committed Teams

The x-axis is the elements of a team, and the y-axis is team stages based on Tuckman’s model. Form and Perform should be self-explanatory; Adjourn is a planned period of reflection, typically quarterly. I’ll go through each region via the Y axis — time!

Stage 1: Form — Designing Your Team Consciously

Think about the last team you were on. How did you start? Did you just sit down at a conference table and start discussing the project? Or did you take time to ask yourselves what kind of team you wanted to be? When you discussed the project, did you discuss logistics and deadlines, or what success looks like?

If you do not consciously design your team, you default into whatever people think is the right way to act in a team. Unfortunately everyone has different ideas about what that looks like. If you want to reduce conflict down the line, it’s better to have a conversation about what the team members want the team to be early.

Goals: I’m going to recommend OKRs — Objectives and Key Results. They work. The team should collectively create their own OKR set in order to fulfill the mandate their company has given them. Read A Meeting to Set OKRs.

Roles: It’s easy to know who is going to be the designer and the engineer, but who will be the facilitator? The tie breaker? The schmoozer?

If we do not clearly decide who will have what role, we’ll default to culture norms, i.e. the woman will end up getting coffee and the tallest guy will make decisions. Discussing what roles are needed, and who wants to fulfill them is crucial for a healthy respectful team.

Norms: This topic gets special love.

Norms

What are norms, you ask me? They are the rules of conduct in a group. Often they are emergent and unspoken. But what if different people have different ideas of what the norms are? They will behave in a way that they think is appropriate, but that behavior will be perceived as inappropriate. And then the judging begins: that person is a jerk, a bully, pushy, pushover, etc.

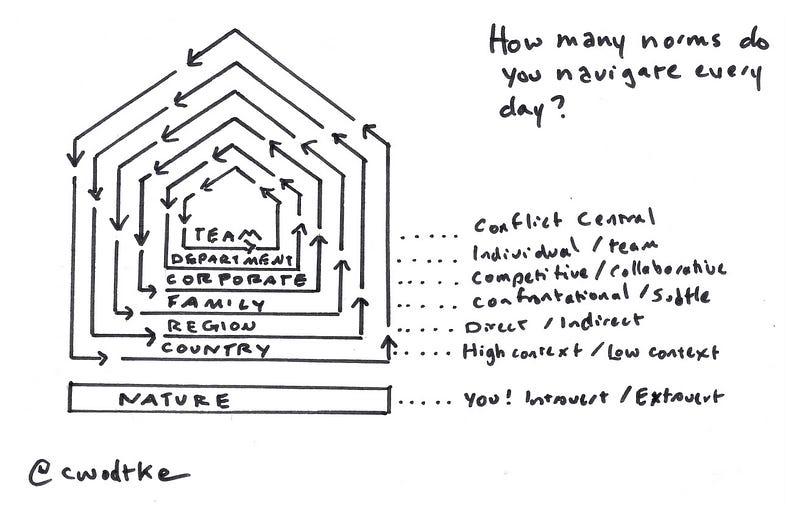

I picture the way norms interact as a variation of shearing layers, the Duffy/Brand model of how buildings are pressured by different paces of change, which can lead to incoherent or even broken spaces.

Americans deal with a huge number of messages about what is normal. We get them from the many cultures that make up this country, from national to regional to familial to corporate. We navigate high context/low context values (value the collective vs value the individual) to cooperative/competitive to conflict adverse/conflict accepting and more.

For example, let’s look at the behavior of interrupting. Let’s say one team member, Margot, came from a big family in Chicago where talking over each other was normal. Only way you could get a word in edgewise! She also works in sales, where fast talking is valued. Now she’s on a team with Jim, who is from Maine, a Quaker, and his family is Japanese-English. Jim thinks Margot is the rudest person he’s ever met, and can’t stand to be in a meeting with her. Margot thinks Jim is a doormat.

I suspect most initial storming is teams trying to normalize varying norms. You could avoid the worst of inter-team conflict by collectively designing the team norms. Instead of letting norms be unspoken and emergent, speak about them and choose what the team will accept and what it won’t.

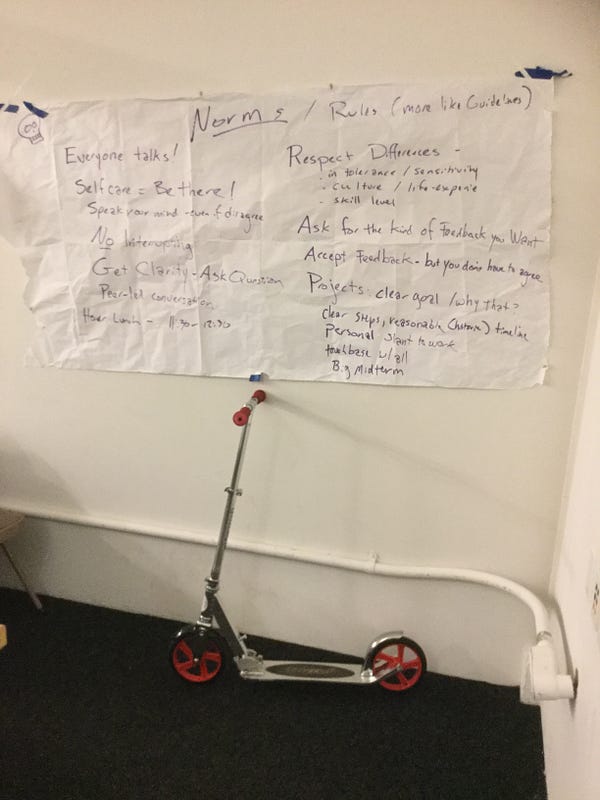

I created a team norming exercise based on one I was taught by Andre Plaut to help classrooms determine their norms. Andre specializes in adult education, and found when classes decide how they want to learn — as opposed to accepting the benevolent dictatorship of the professor — they learn more quickly and completley.

Exercise for Team Norming

Picture the best team you’ve ever been on. The one where you felt you were part of something special. Can you recall it’s characteristics? What made it so awesome? Write them down on post-its.

Now picture the worst team you’ve ever been part of. You know, you wake up each morning dreading that you’ll be facing those people. What made it so dreadful? Write them down.

Take a moment to stack rank your issues. Then share your top three goods and top three bads with your team.

Finally, make a list of rules for your team. It should be easy to think up rules after a moment of reflection on your experiences. Call them out to the facilitator, and have them listed on a whiteboard to butcher paper — something that invites editing and updates.

When I run this exercise, I question the “rules.” If someone says, “speak your mind.” I’ll ask,

- What does it look like when someone “speaks their mind.”

- Why does that rule matter?

- How can we tell if people aren’t following the rule?

- How do you plan to call each other out if someone violates this rule?

The rules need to have the same meaning for all team members. I often have to get clarity around a phrase that “everyone knows what it means,” like “speak your mind.”

Many teams in the Silicon Valley are composed of people from both High Context and Low Context cultures (cultures that value the collective vs cultures that value the individual). A rule like “speak your mind” has a very different meaning for a person from China, a person from Holland and a person from Texas. By describing what it looks like to speak your mind, it’s recognizable by people whose culture doesn’t favor direct confrontation. Some people need formal permission to speak up.

Let’s say Jim suggests the rule, “No interrupting.”

Margot is confused, “What do you mean?”

Jim, “it’s rude.”

Margot, “I don’t think it’s rude. It’s important to get your ideas out while they are fresh.”

Jim, “But when you interrupt me, I forgot what I’m saying. It’s upsetting. I feel like my opinion isn’t valued.”

The facilitator can then ask others what they think (if they don’t jump in.) The group will decide if interrupting is ok, at which point the facilitator can ask the group how to help Jim make sure he can participate. Or the group may decide interrupting is not ok, which means they need to figure out how to help Margot adjust. Two things need to happen

- pick what is acceptable behavior in your group

- decides how to help everyone live with that choice.

After you’ve got about ten rules people believe they can live by, ask “how are we going to make sure we don’t forget these?” Nudge people toward a rhythm of check-ins, be it monthly or quarterly.

Discussing check-in timing is often a good conversation all by itself. It gets the team thinking about commitment and accountability, which is critical later.