The class I teach is called “Story,” and the first assignment was to give a “TEDette.” I defined the project as a five minute talk using a personal story to make an audience care about a scientific principle. Y’know, like TED.

My Stroke of Insight was our model; we dissected how Jill Bolte Taylor interwove her story of experiencing a stroke with scientific understanding of how the brain functions and the role of the left and right hemispheres. Then, just I prepared to transition into studio time:

“How do you give a great presentation,” John blurted out, raising his hand and asking the question in one swift move. He leaned forward, hungry for an answer, hungry to be great. I knew that look, I’d felt it on my face often enough.

A few years ago, I’d been asked to speak at a conference in Prague about my experiences running product teams in the Silicon Valley. I was oddly nervous. It was not the first time I’d been on stage, but it was the first time I was talking about managing product. I was also nervous because I knew I’d be talking about a topic I was planning to write a book about. I wanted this talk to go well, or else maybe I was wrong about writing the book.

Oh, and an acquaintance I truly admired was in the audience. We’d been casual friends for a long time, seeing each other every year or two at an event or conference. We both wrote our books at the same time. His outsold mine at least by a factor of five. We both started consultancies at the same time. His made it, mine went under. You know that person, the one you really like yet you find yourself competing with. Because you’re human. Or stupid. And you feel just once you’d like to beat that friend.

He was keynoting in Prague. I was the product track Saturday afternoon.

I found myself horrifically blocked trying to write this talk. It was worse than I’d ever experienced. On the plane over, I sat with Powerpoint open in my lap, and I’d just stare at it. For eleven hours. At night I’d wake up every few hours, partly jetlagged, but partly to write down a fact or insight I’d had on for the talk in the notebook next to the table. My mind was in a sumo match with this talk, and it couldn’t stop fighting.

The day of the talk, I had a brief moment of relief. I could feel it wasn’t a great talk, but it was full of great information. I hoped that would be enough. And my friend wasn’t in the audience. Then, as the organizer introduced me, my pal slid in the back of the room and sat down. The knot in my stomach tightened.

I’m lucky. I’m one of those people who comes alive on stage. No idea why, but once I step into the talk, I am in it. I managed to do what had been asked of me: “share my learnings about managing product at top companies.” I was nervous, I talked fast, I came in short. I gave a 25 minutes in a 45 minute slot. But luckily there were plenty of questions, and we filled the time. But as the first person stepped up to the mic to ask a question, I saw my friend slip out the back, as quietly as he slipped in.

I realized then I’d have to ask him for feedback.

I hate feedback. If it’s my work at a company, fine. My design, my product, my spec: go ahead and rip it apart and make it better. But if it’s something I crafted that represents me — a book, a talk, an article — I suffer from “my baby” syndrome. I don’t want to hear my baby is ugly. Despite that, this talk was the first time I was giving a talk I planned to be giving again and again,and writing a book about. I had to suck it up. So after his keynote (fascinating!) I went up to my friend and after complimenting him on his talk, I asked. “Well, I saw you made my talk. Um, whaddya think?”

He looked me in the eye, face placid, but his jaw muscle moved slightly. Gritting his teeth perhaps.

“It had good information in it. But I’m not sure it hung together.” It was gentle feedback, but he was right. I wasn’t great. I was just another fact-spewer.

In that moment, I committed. I would stop making it up. I’d stop just showing up on stage and trusting that being smart was enough. I would get good. I would aim to be great.

And now, three years later, John wanted to know what I’d figured out. I went to the whiteboard.

Start with the Right Structure

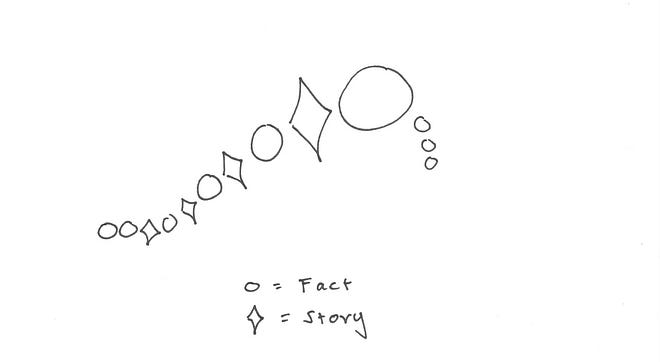

Everything we enjoy — movies, tv, novels — all have a structure that guides us from curiosity to excitement to satisfaction. A great speech does this too. A bad speech just strings together facts like beads on a necklace. A really boring necklace.

There are quite a few ideas on how to structure a talk.

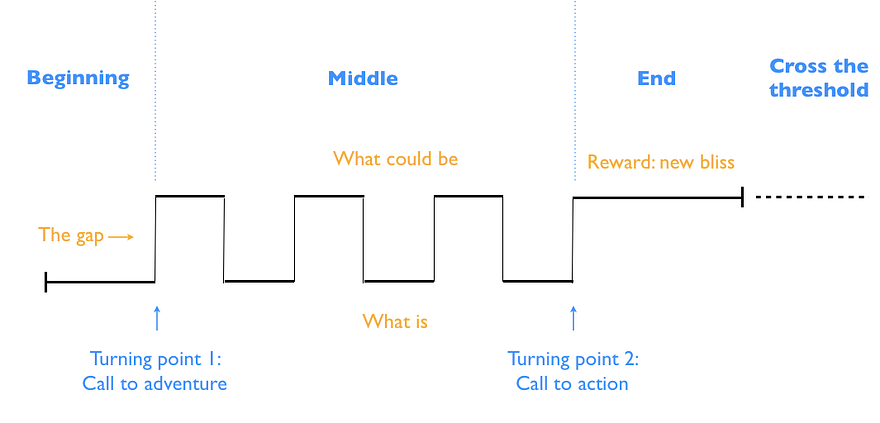

In Resonate, Nancy Duarte shares an insight she had about great speeches. She says they all move from what is and what might be. (She throws a little hero’s journey in there too)

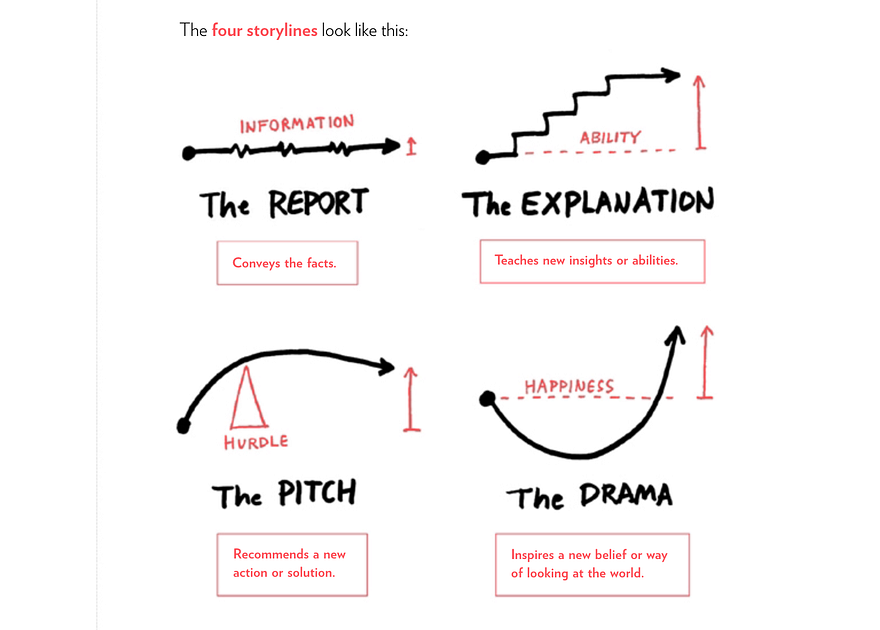

In Show and Tell, Dan Roam has four structures he recommends:

Because Dan is a visual thinker, he draws out these formats, making it easy to see which are dynamic and compelling and which are not. Anyone can recognize “the Report” as the boring necklace of facts. When was the last time you enjoyed a report?

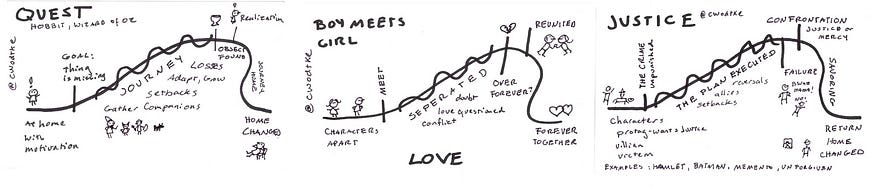

Finally, in Give Your Speech, Change the World, Nick Morgan recommends all speeches be based on one of the five archetypal stories: The Quest, Stranger in a Strange Land, Rags to Riches, Revenge, and Boy Meets Girl.

This was the book that led me to my next realization.

Become Story Driven

Six months after Prague I got an email. I had submitted my product talk to another conference, in Amsterdam. And I’d been accepted. My mouth went bitter with the taste of my failure in Prague. Here we go again.

This time, it had to be different. I had committed to being great. Plus, I’d begun writing my book, and I needed to drive presales. So I made three key changes to my talk.

First, I focused the talk on just one aspect of the work: using OKRs. I have learned that it is more effective to say fewer things, better.

Second, I decided to use a story to engage my audience. In my book, tentatively called The Executioner’s Tale, I had decided to write a fictional case study as the opening. I had read a study that showed attention, engagement and retention was improved by using story as a format for delivering information. And why would I spend a year of my life to write a book no one would remember?

I committed so deeply to story that I hired a fiction editor — a woman who edits romances and science-fiction — to edit my book. My book had to have a thrilling plot with plenty of tension and drama. I dreamed of making a business book that was also a page-turner.

So why not do that with my talk?

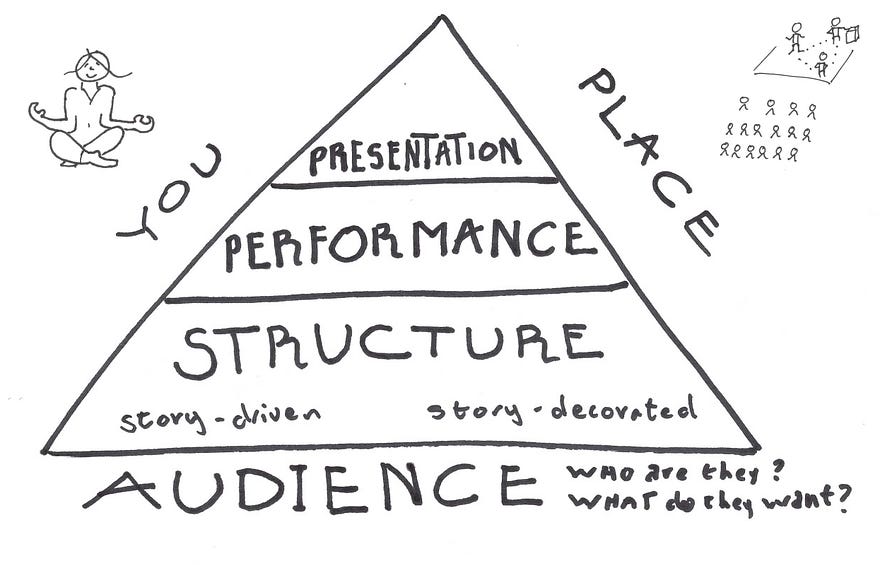

There are two ways to use story in a speech. I call them story-decorated and story-driven. When I say Story, I mean something very specific. I mean this.

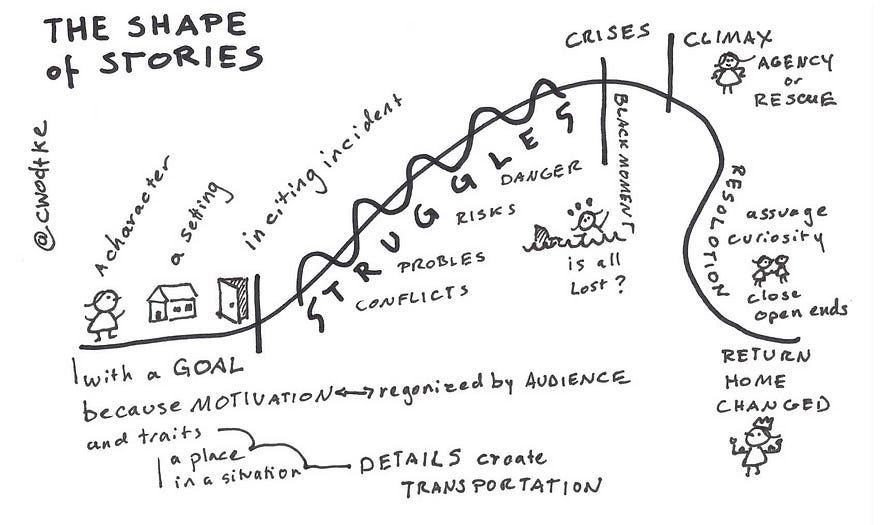

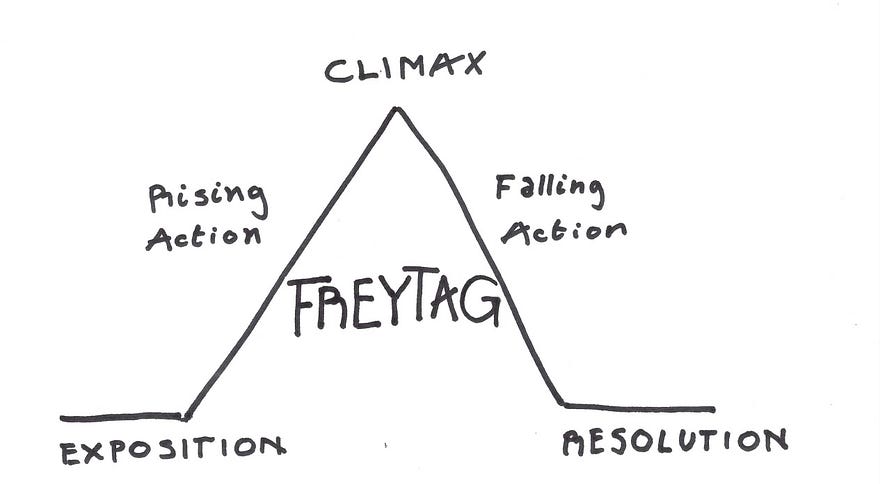

First there is an exposition: how the world is now. Then an inciting incident: why does our protagonist choose to change? Then we have struggles, also known as try/fail cycles, where our character faces increasingly difficult challenges often peaking at a crises. Finally there is a climax, where the problem is solved. Then all is left is the resolution: tidy things up and return home changed.

At a minimum, a story must have these three elements: a situation, a struggle, and a solution.

Without this shape, you don’t have a story, you have an anecdote. An anecdote is a snippet like “I went to Trader Joe’s and my checkout guy went to the same art school as me! Isn’t life crazy?” Anecdotes are charming and they are often interesting, but they aren’t as compelling as a full-fledged story.

I said earlier I made three key changes to my speech. But the third change was not to my speech, actually. It was to me. I hired an acting coach.

My coach taught me that your body is your instrument, and you must tune it. She taught me voice exercises, breathing, and how to walk the stage. She taught me where to look into the audience and how to pause for effect. And while I still play my instrument like a five year old plays chopsticks on the piano, I made a big leap forward.

When I stepped on stage in Amsterdam to give my talk, I was not a lecturer. I was a storyteller.

First, I opened my talk with a short zen story. Then, I told my fictional case study. I introduced my characters and gave them goals and motivations. I made them struggle and I made them fail. Throughout I introduced key facts about OKRs, decorating the story with knowledge. Finally, at the end of the talk, I shared a personal story about how I used OKRs to get my own life back on track.

After, I was shaken. Telling a story on stage when everyone else was professionally reciting facts was scary. Sharing a personal struggle was terrifying. I had to admit I was less than perfect in front of people!

I had just been a bit too brave, and I was considering vomiting. I headed to the ladies room to wash my face. But before I could even open the door, a woman stopped me.

“Thank you for that. Your talk… I loved it.” She took my hand, and my nausea subsided, and my eyes filled with tears. It had worked.

And so it went for the next three days of the conference. I was stopped every few minutes by someone thanking me for the talk. And every time I’ve given it since, I’ve gotten the same reaction. I’m 99% sure it’s because humans are wired to respond to story.

The Executioner’s Tale — now retitled Radical Focus, after my book — is an example of story-driven structure. While it does have a mini-story for an opening and closing, the bulk of the presentation is organized by the arc of the fictional case study, much like My Stroke of Insight.

Another example of a story-driven talk is Brene Brown’s The Power of Vunerability. She opens with an anecdote about being called a storyteller. Then she moves into her bigger story, how her research caused her to question her most profoundly held beliefs and reinvent herself. Along the way, we learn the science behind her research. But it’s never dull, it’s always personal, and it’s made cohesive with story.

Story Decorated

I mentioned another way to use story in a presentation. I call it Story-decorated. To see it in action, watch Ken Robinson’s number one most watched TED talk, Do schools kill creativity?

In it, Robinson talks about the failure of education to allow students to fulfill their potential. He has a series of points he wishes to make and every so often he decorates his points with a personal story, an anecdote or a joke.

Yet… yet… there is something more going on here. Even though he is decorating his necklace of facts with diamonds of stories, he’s doing something beyond that. His facts follow the progression of a story. He opens up with the status quo (exposition), he introduces the problem (inciting incident), he introduces one problem with current education, then the next, each problem more disturbing then the next. The jokes and the stories create a rising tension as we wonder how bad things will get and he continues to refuse to give us the fix. Then he foreshadows his talk’s climax with a story about a girl who couldn’t sit still, Gillian. Her mother takes her to visit a specialist who realizes the only thing that’s wrong is the school. “Gillian isn’t sick. She’s a dancer.”

This story is followed by the factual climax: the solution he proposes. Education must diversify, embrace creativity and change. He mirrors his decorative story’s climax with his fact-based story’s solution.

Facts, if ordered along the the story arc AND contextualized with real human stories, can be just as powerful as a story driven talk. Amy Cuddy’s Your Body Language Shapes Who You Are is even a more extreme example. Despite TED’s typical insistence on personal stories, Cuddy manages to avoid any personal revelations until the very end, as a coda. But she orders her insights from trivial to interesting to critical, so her talk is increasingly more exciting and compelling. The try/fail cycles are replaced with mystery/learning cycles with increasing stakes in our everyday life.

I have another wildly popular talk, on how to use Story at work. I’ll admit I had been lazy with this talk, as I wasn’t very serious about it, and hadn’t bothered to create a framing story. In fact, there is nothing recognizable as story in it, just a few anecdotes here and there. I couldn’t figure out why people loved it. But after studying Ken Robinson and Amy Cuddy, I have a theory.

The facts and insights in my Story talk grow increasingly important to my audiences’ success at work. The audience is the protagonist. The inciting incident is the moment they sit down in their chairs to listen to me. We go through each insight — what story is, how ot use it to persuade, to design, to communicate value — until the climax where they know they’ve learned something they can take back to the office. The talk has the shape of story, and the audience is the hero.

So: Story.

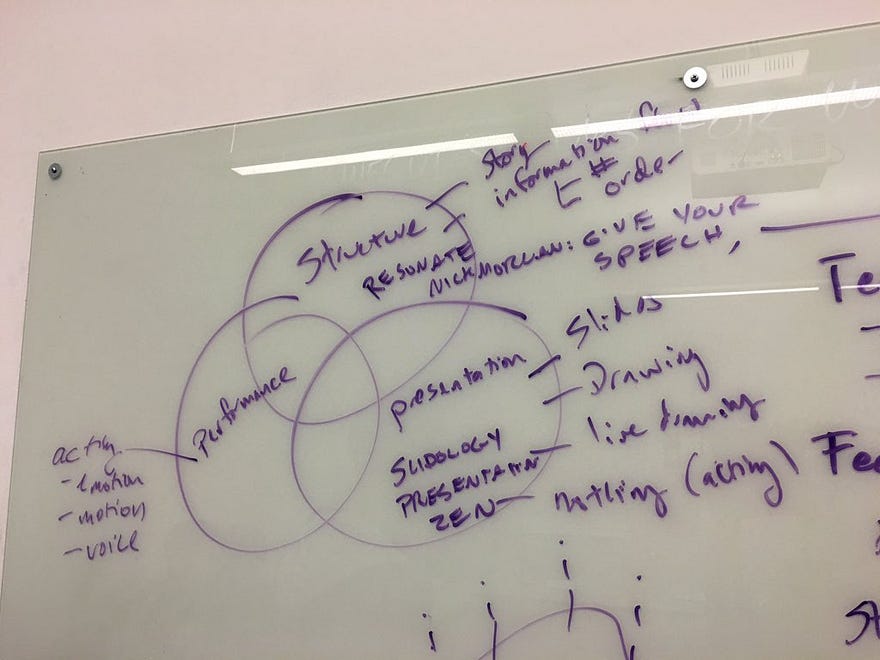

I believe if you want to give a great presentation, you should master three things: your structure, your presentation and your performance. But I think rather than a Venn diagram, I’d draw it as a pyramid, because it all starts with Story.

Presentation refers to the look of your talk, and there are so many books on that from Slide:ology to Presentation Zen. Performance is you: your voice, your posture, your presence. You can take acting classes or join toastmasters to get those skills.

But they are both just surface polish. Neither of them mean a thing if you do not get your structure right. The best structure is a story structure. It intrigues, excites and satisfies the way no quantity of brilliant insights and validated facts ever can.

So before you visit istock photo to find that perfect image, before you crack open Keynote or PowerPoint, take the time to find your story.

Coda

I sent this article to my pal Indi Young, and she said “What happened to John?”

John gave a terrific TEDette about stage fright. He told a story of a presentation class he almost failed. He interwove the biological reasons behind why we get stage fright with his struggles with insomnia, nausea and his voice cracking with terror. He stalked the stage like a caged tiger as his hands shook, betraying the personal nature of the talk.

And he was great.

Addendum

If you’d like to see me develop this article into a short book on presenting, including performance and presenting beyond slides (yawn) tweet at me. I’m@cwodtke https://twitter.com/cwodtke

This is the talk I gave in Amsterdam: The Executioner’s Tale.

This is the book it became:

How do you inspire a diverse team to work together, going all out in pursuit of a single, challenging goal? How do you get your team to commit to bold goals? How do you stay motivated despite setbacks and disappointments? Get Radical Focus.

And I write a lot here http://eleganthack.com/