How do you avoid the slow waterfall of goals?

A draft of a chapter for Radical Focus 2.0. I write about high performing teams, check it out.

It’s probably my fault and I am sorry. But like Lean Startup, I experienced and worked with OKRs initially with startups. That meant cascading OKRs was reasonably simple and could be a true “cascade.” But this doesn’t scale AT ALL. And just as Lean had to adapt to enterprises wanting some of that speedy iterative goodness, OKRs need to adapt also.

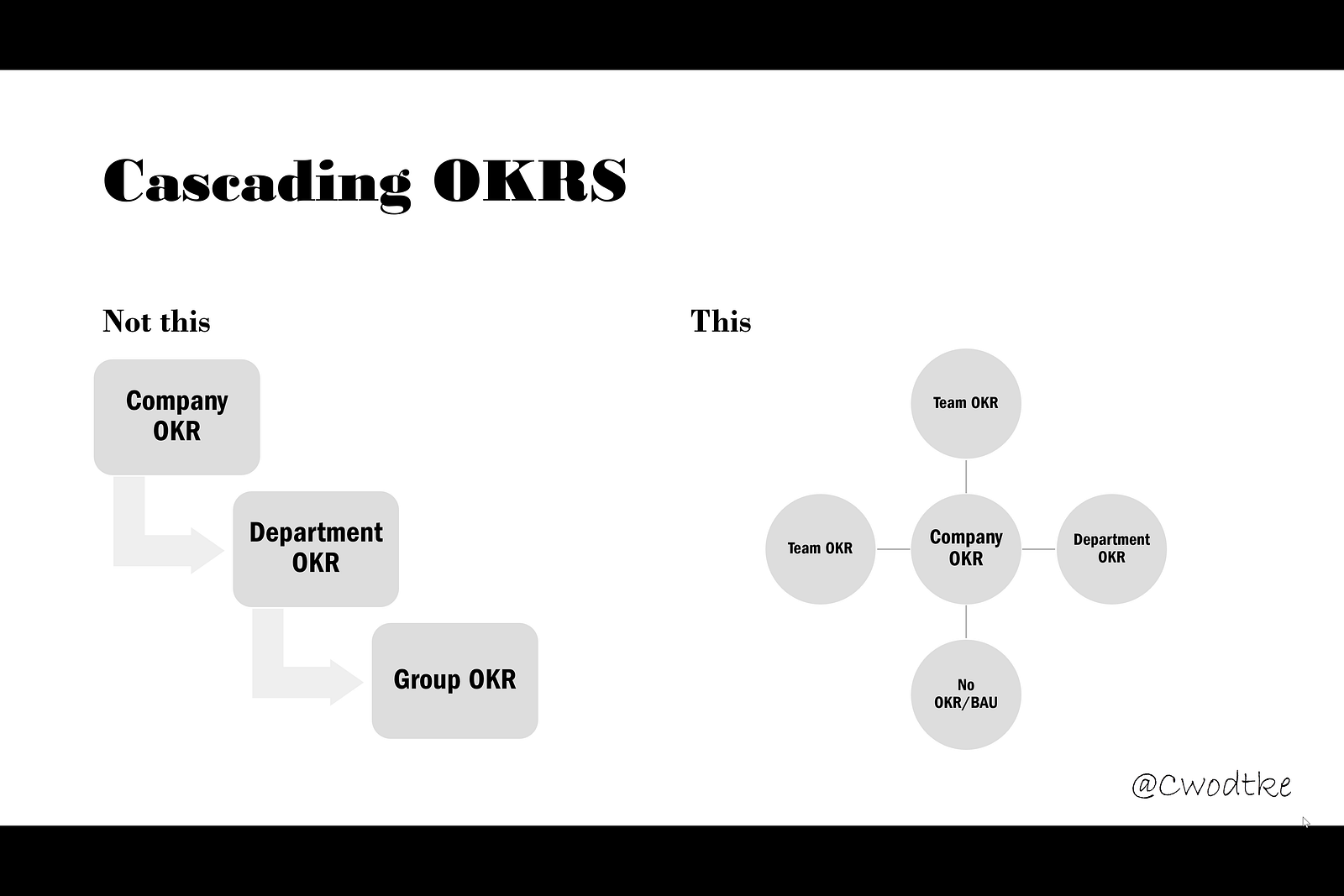

When the organization has only one or maybe two levels of hierarchy, a straight cascade might make sense. The executive team sets the company OKRs, then departments (product, marketing, sales) can set theirs. Engineering and Design can skip having OKRs for their departments, because 99% of their work is with the other teams.

But when a company grows, it changes. I heard a story about a (real but I won’t name) new CEO who came into a very large company that was on the skids and tried to use OKRs to straighten it out. Sadly, she was a micromanager, and it took a month to get her to approve all the department head okrs.

Let me say this clearly and loudly: OKRS are NOT for Command and Control. Do not use OKRs if you want to control people’s activities. Only use OKRs if you want to direct your people toward desired outcomes and trust them enough to figure out how. OKRs ONLY work for empowered teams, otherwise they are a travesty (a travesty reminiscent how how Agile is implemented in most companies, so not that shocking. But still upsetting.)

So what should you do?

Assuming you have run your pilot with a high performing self-sufficient team, assuming you have adjusted the setting, check-in and evaluation process to your culture: assuming you know what you are doing and are ready to scale, then this is what has been proven to work.

Trust your teams to set their own OKRs based on company strategy. Trust your team to know how to make them happen. Trust your teams.

How Distributed OKR Setting Works

It starts with a mission. Most companies have decent missions, and a mission is an objective for five years (a mission is not forever. Companies, like people do change over time.) Once you know your mission, you can think about what this year is all about. Are you moving into new markets? Are you diversifying your product offering? You can have more than one, but one is better for both clarity and memorability. Your business strategy informs your annual objective. If you don’t have a business strategy, you can’t use OKRs.

Then you can state what the company key results will be, which adds further clarity to the objective and also memorability. Keep them short and simple. You can use metrics reviews for deep dives into other critical numbers but don’t overwhelm everyone with a thousand details that don’t affect them.

Now you are ready for quarterly OKR sets.

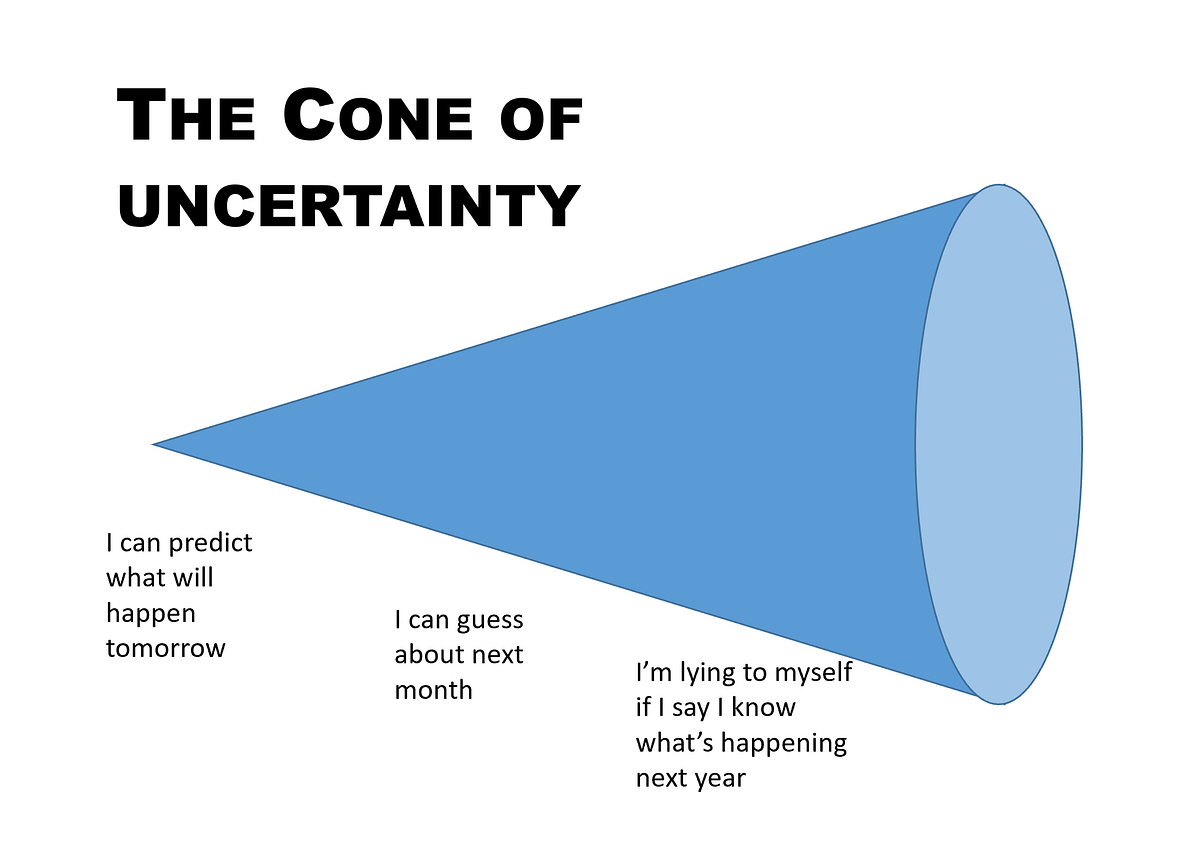

The exec team sets four objectives and three key results: the first quarter objective with its accompanying key results and then three more candidate objectives for the other three quarters. I recommend this approach because of the cone of uncertainty. The cone of uncertainty states that the farther we predict into the future, the less accurate our predictions become. But without a long term goal, it’s hard to make long term plans. So this approach saves you the time of pinning down KRs (usually the hardest and slowest part of the process) but still lets you do long term planning. Once you have these things in place — mission, Q1 OKR set and 3 more candidate objectives — you can make them available to everyone in your company.

Next all self-sufficient teams can set their OKRs. These are autonomous, empowered teams that have all the resources they need to proceed. It’s often product teams that have dedicated design and engineering resources (and more, depending on your company type.) These OKRs can be looked at and discussed with the direct manager of the teams. This “review” is more for the manager to share any intel they have from being able to see what’s happening in other groups rather than to “approve” them.

This can also be a peer review. Teams can share their OKR sets with other teams to get feedback and raise awareness of what the teams will be focusing on.

Two groups — other than product teams — that are often self sufficient are marketing and sales. They can have their own OKRs but those OKRs should reflect the company OKRs. If the company is focusing on social media, marketing and sales should also consider how they can use social media to reach new customers.

Service Departments

The service departments can decide if they wish to set OKRs for areas they wish to improve at as a service with the expected time remaining, which is often only 5–20%. Service departments can include but are not limited to

- Engineering (including ops)

- Design

- Legal

- Customer Service

- Marketing

- Finance

Service teams do NOT have to wait for the self-sufficient teams to set their OKRs unless they think the workload is highly unpredictable. For speed, it’s better they set OKRs are soon as possible, even if they need to be tweaked once the self-sufficient teams announce their OKRs. If teams do NOT know how much time they can control each week, measure your workload for a quarter before you set OKRs.

Some groups, such as legal or finance, have more predictable schedules than product teams. They do not always need OKRs and can use health metrics to keep quality at a steady state. In the chart I refer them to BAU — business as usual.

Within 48 hours of the company OKRs are set the rest of the company should be able to publish their OKRs. THE BEST IS THE ENEMY OF THE GOOD. A short review process — 24 hours if possible — allows teams to look at what other people are doing and adjust their own OKRs or critique others. Anyone can critique anyone else’s OKRs: this should be a process in which the entire company is helping everyone in the entire company get better. We succeed together, or not at all. After this window closes, you live with it until next quarter when you get a chance to get better at this. Analysis paralysis is a real thing, and it’s critical to plan to avoid it. Get OKRs into play so you can learn how to do them better next time.

Of course when you review, you may find someone is working on the same problem your team is. ITS OK. I recall chatting with Google Ventures Partner Ken Norton about when he first started at Google. Google was already huge at that point and they had an unintuitive approach to duplication of effort. There is no way to know what team will succeed and how they will succeed, so don’t worry about duplication until you have multiple successful options. I think this is the right way to look at innovation: it’s more important to be effective than efficient. Efficiency kills innovation.

There is a schedule that looks a bit like this

- Grade OKRs two weeks before quarter ends (there are very few hail mary’s possible in the last two weeks, unless you’re in sales.) Determine if you should move to the next expected objective, change it or have a do-over.

- Annual OKRs are set by execs, typically at an offsite (for focus reasons.)

- Two weeks or so before EOQ the execs set company OKRs. This will be a two-hour meeting once you’ve got the hang of OKRs, but at the beginning of your process, reserve more time. I recommend scheduling 3 two-hour meetings, and think how nice it will be to cancel them if you don’t need them!

- Publish company OKRs a week before quarter ends. Teams and departments set OKRs.

- Publish team and department OKRs (if departments have them)

- Short review period

- Short revision period

- Hit ground running on day one of new quarter.

This is the only way to scale OKRs without dragging your company to a halt every quarter. It requires you to do several brave things

- Hire well

- Give up control of tactics to achieve company goals

- Trust your teams

But if you don’t have trust, OKRs weren’t going to help much anyhow.