If you plan to do NaNoWriMo, you’re going to write 1,667 words a day. That’s a lot of words to write everyday. Whether you’re a plotter or a pantser (if you like to outline, or just write and see what comes up), you are going to get stuck. You can always “freewrite,” which looks like this:

“Oh god what do I write I’m totally stuck, I should never have signed up for this, my characters are stupid except the duck, he’s kinda interesting, I wonder why he limps? maybe he was a spy in the last war…”

Freewriting sometimes works, and always adds to your wordcount. But I find these blobs of text super annoying in revision. I prefer to look for more useful ideas for inspiring material that might actually contribute to the final draft.

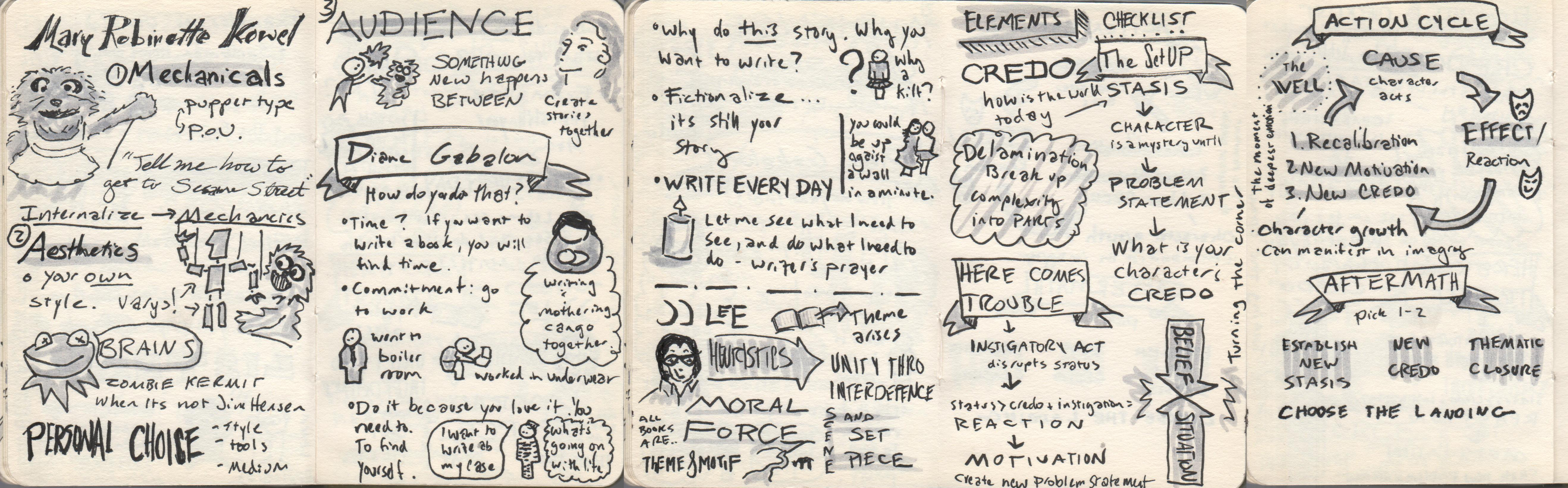

I wrote a big synthesis of writing advice up here: The Shape of Story and it makes for good October reading (I hope!) It covers plot and characters and many other helpful big picture ways to think about your book. It’s how you make a good book.

However, when you’re in the trenches of November, staring at the blank screen, sometimes a writing a good book isn’t as important as making words happen. After all, isn’t quality what revision is for? The frameworks below can get your fingers tapping the keyboard once again.

Goal, Motivation, Conflict

Debra Dixon introduced this concept in her eponymous book, GMC: Goal Motivation, Conflict.

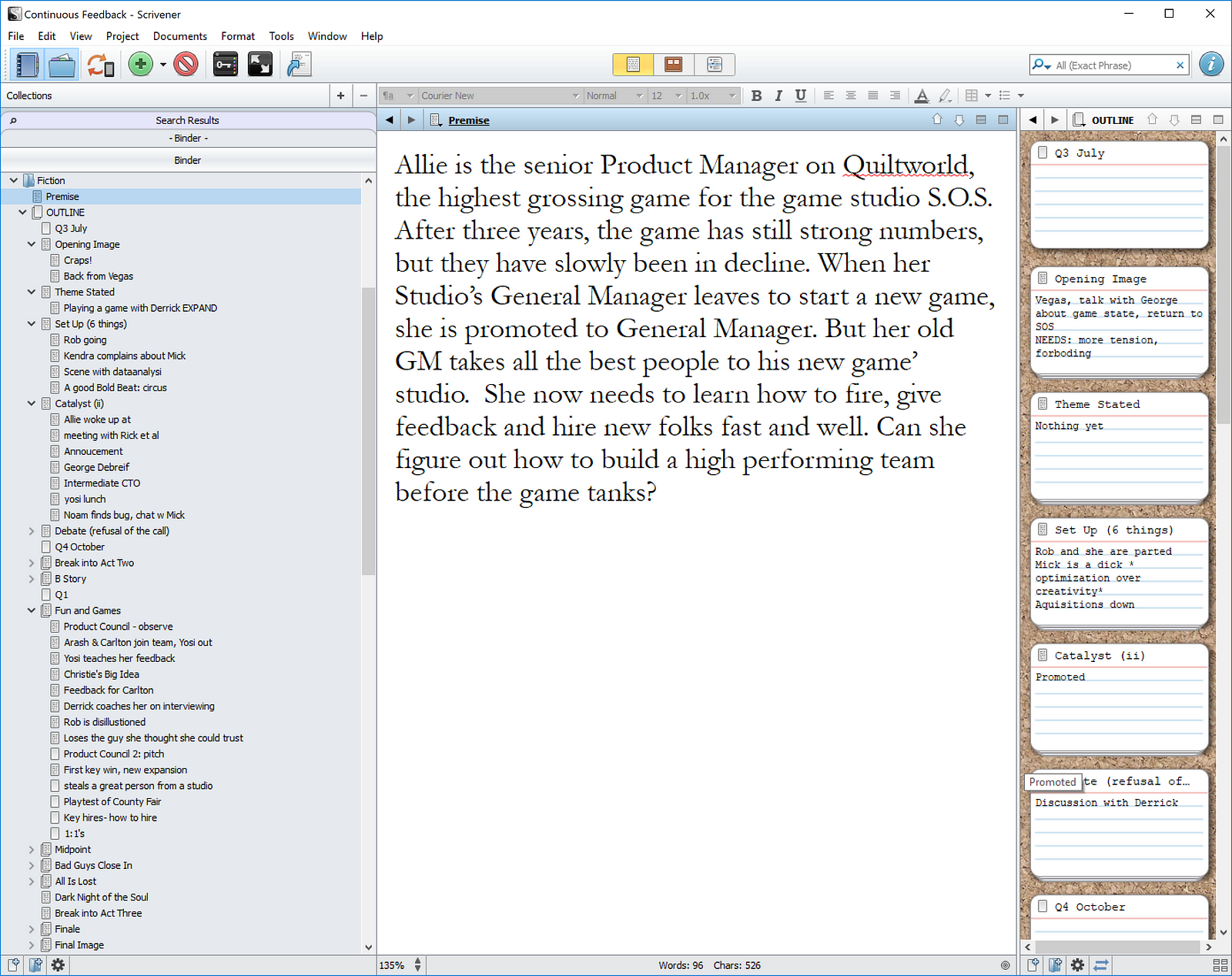

Each character in your book should have an internal and external Goal, Motivation and Conflict. In my book, I had a senior product manager promoted to general manager. Her external goal was to be an effective manager, because she wants to keep the promotion, but the former GM just stole all her best people. Her internal goal was to learn how to be a great leader, so she can run her own company someday, but she lacks the skills to manage effectively.

Now that I know this: bingo. I’ve got to write scenes where the audience sees these goals, motivations and conflicts! Show not tell, right?

As well, a good antagonist should have a GMC as well, as well as a supporting character, a romantic lead… more scenes, good word count galore! Create character sheets with GMC’s, and you’ll quickly have a rough outline of scenes you need to write.

Yes And, No But

I learned two great frameworks from Jack Bickham’s Scene and Structure. The first framework is called “Scene and Sequel.” This is a framework for elements in a unit of your novel (scene/chapter/etc.) I’ll admit it’s a confusing nomenclature, since we usually think of a scene as containing both what Bickham is labeling “scene and sequel.” We can call it “Attempt/Consequences” if you prefer.

A Scene (attempt) has the following three-part pattern:

- Goal (not the big overarching goal in GMC, but a small step toward it.)

- Conflict

- Disaster

A Sequel (consequences) has the following three-part pattern:

- Reaction

- Dilemma

- Decision

The second big idea from Bickham’s work is the “Yes, but” and “No, and” pattern. You use it to describe the disaster….

Conflict is what keeps readers engaged. It also will help you, the writer, keep you engaged and writing. So any time you get stuck, ask yourself, how can I make my protagonist suffer? Bickham suggests two ways:

YES, BUT: Protagonist gets what they wanted — “Yes” — but it makes things worse/something else happens to complicate matters — “But.”

NO, AND: Protagonist fails — “No” and it makes the situation even more challenging. Maybe the need to try a harder plan, maybe they’ve been caught in the act — “and.”

“Yes, but” example: My character might try to poach a really good engineer from another group because she hates hiring. It’s so slow! She succeeds, but the engineers boss finds out, and she’s made an enemy that will block her proposal for a new feature to the product council. She’s upset, but she can’t un-offer the job. She’s going to have to find a way to make it up to the engineer’s boss before Tuesday, when the product council meets.

This could be a “No, and” example if she failed to make the hire, but she still made an enemy and she still has to fill the position….

That’s worth 1000 words at least! Remember:

“Struggle makes story”

The Beat Sheet

Somewhere around thirty thousand words, I hit the dark night of the soul. I had too many words and couldn’t hold the plot in my head anymore. I couldn’t figure out where in the story I was! I write in Scrivener, which allows me to see both the outline and the writing (word and Google docs can do this also, but it’s easiest in Scrivener to move scenes around)

I dropped the beat sheet outline into my novel, placed my scenes in his guide, and found a bunch more scenes to write.

I don’t think the beat sheet is the be all and end all of plot structure. But compared to three-act plot structure, or seven point, or story circles, etc, it’s a lot more helpful when you just need someone to tell you what to write. It’s specific and proscriptive enough to provide scaffolding when you are lost and give you ideas for more scenes to write. It almost doubled my word count and dehorked my plot.

THE BLAKE SNYDER BEAT SHEET (aka BS2)

- Opening Image — A visual that represents the struggle & tone of the story. A snapshot of the main character’s problem, before the adventure begins.

- Set-up — Expand on the “before” snapshot. Present the main character’s world as it is, and what is missing in their life.

- Theme Stated (happens during the Set-up) — What your story is about; the message, the truth. Usually, it is spoken to the main character or in their presence, but they don’t understand the truth…not until they have some personal experience and context to support it.

- Catalyst — The moment where life as it is changes. It is the telegram, the act of catching your loved-one cheating, allowing a monster onboard the ship, meeting the true love of your life, etc. The “before” world is no more, change is underway.

- Debate — But change is scary and for a moment, or a brief number of moments, the main character doubts the journey they must take. Can I face this challenge? Do I have what it takes? Should I go at all? It is the last chance for the hero to chicken out.

- Break Into Two (Choosing Act Two) — The main character makes a choice and the journey begins. We leave the “Thesis” world and enter the upside-down, opposite world of Act Two.

- B Story — This is when there’s a discussion about the Theme — the nugget of truth. Usually, this discussion is between the main character and the love interest. So, the B Story is usually called the “love story”.

- The Promise of the Premise — This is when Craig Thompson’s relationship with Raina blooms, when Indiana Jones tries to beat the Nazis to the Lost Ark, when the detective finds the most clues and dodges the most bullets. This is when the main character explores the new world and the audience is entertained by the premise they have been promised.

- Midpoint — Dependent upon the story, this moment is when everything is “great” or everything is “awful”. The main character either gets everything they think they want (“great”) or doesn’t get what they think they want at all (“awful”). But not everything we think we want is what we actually need in the end.

- Bad Guys Close In — Doubt, jealousy, fear, foes both physical and emotional regroup to defeat the main character’s goal, and the main character’s “great”/“awful” situation disintegrates.

- All is Lost — The opposite moment from the Midpoint: “awful”/“great”. The moment that the main character realizes they’ve lost everything they gained, or everything they now have has no meaning. The initial goal now looks even more impossible than before. And here, something or someone dies. It can be physical or emotional, but the death of something old makes way for something new to be born.

- Dark Night of the Soul — The main character hits bottom, and wallows in hopelessness. The Why hast thou forsaken me, Lord? moment. Mourning the loss of what has “died” — the dream, the goal, the mentor character, the love of your life, etc. But, you must fall completely before you can pick yourself back up and try again.

- Break Into Three (Choosing Act Three) — Thanks to a fresh idea, new inspiration, or last-minute Thematic advice from the B Story (usually the love interest), the main character chooses to try again.

- Finale — This time around, the main character incorporates the Theme — the nugget of truth that now makes sense to them — into their fight for the goal because they have experience from the A Story and context from the B Story. Act Three is about Synthesis!

- Final Image — opposite of Opening Image, proving, visually, that a change has occurred within the character.

- THE END

Get Save the Cat to learn more tricks from screenwriting (and more profoundly understand these beats.) As well, Save the Cat Goes to the Movies can help with genre beats (i.e. what scenes do you write for a heist vs a romance.)

Write On!

Any writer reading this is probably a little horrified. These frameworks may appear a big hamfisted. But anyone who has done NaNoWriMo is probably a little relieved. Me, I’m both. Part of me feels these are formulaic. The other part of me knows that formulas can keep you going when the muse refuses to nurse you anymore.

Writing a novel is an exercise in tolerating ambiguity. You leap into November 1st with very little idea what November 30th will look like (even those outliners!) When you’ve hit 20 thousand words and your mind is blank and Thanksgiving is around the corner threatening to disrupt your rhythm, you ditch your pride and embrace the tricks that crush writers block and further your story. These helped me… I hope they help you!

Excelsior!