Recently, more than the color of the leaves on the trees has been changing. Everyone seems to be redesigning. Apple’s OS7, Slate, new features on Twitter, Google, the Yahoo logo (and much of Yahoo) — even my kid’s school website. And users are angry, annoyed, exhausted, eye-rolling… not delighted.

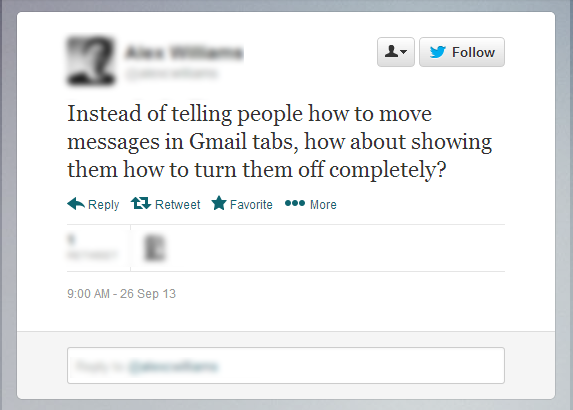

This user does not want your “improvements”

And so the usual comment comes: users hate change.

Now this is a funny comment, considering that the entire silicon valley has been built on the fact that users like change so much they pay for it. If users hated change, Google would have failed, and we’d be happy with Altavista. Facebook would have failed, because Friendster was enough. Paypal would have failed, because, you know credit cards. And Skype? whatevs, I got a phone in my house dude!

What’s not being said is Users don’t hate change. Users hate change that doesn’t make things better, but makes everything have to be relearned. In fact, users don’t like change that might improve their lives if they don’t perceive the value of that change.

In Eager Sellers and Stoney Buyers, John Gournville points out that getting consumers to adopt a new product is incredibly difficult

“First, people evaluate the attractiveness of an alternative based not on its objective, or actual, value but on its subjective, or perceived, value. Second, consumers evaluate new products or investments relative to a reference point, usually the products they already own or consume. Third, people view any improvements relative to this reference point as gains and treat all shortcomings as losses.

Fourth, and most important, losses have a far greater impact on people than similarly sized gains, a phenomenon that Kahneman and Tversky called “loss aversion.” For instance, studies show that most people will not accept a bet in which there is a 50% chance of winning $100 and a 50% chance of losing $100.The gains from the wager must outweigh the losses by a factor of between two and three before most people find such a bet attractive.”

So when a big change comes, the end users is focused on what they have lost: productivity, comfort, familiarity. And the users weight that loss as three times more important that any gain that company professes to offer. The exact same math applies to redesigns: you moved my cheese and I am not happy about it.

Add to that sense of loss a loss of happiness. Research has long shown that the #1 predictor of happiness is a sense of control. Angus Campell says in Psychology Today

“Having a strong sense of controlling one’s life is a more dependable predictor of positive feelings of well-being than any of the objective conditions of life we have considered,”

Now let’s imagine users of a product. They know where everything is. They know how it works. And one day you change it. And because you think you are Apple (or because you are Apple) you change how the product looks and works without one word of explanation of where you put key features like search or the navigation system. And suddenly the users have lost their sense of control and their happiness along with it without one word from you on how their life is about to get much, much better. You’ve basically snuck into their house and rearranged their living room furniture to a more pleasing (to you) configuration. Without permission or warning.

Or perhaps you take the Slate route, and tell people where all the features went, but not why they should care.

The overlay is a nasty “best practice” that is migrating from lazy app onboarding to sloppy web design. Why is it a bad choice? You interrupt your users from the goal they were pursuing to ask them to memorize how you’ve rearranged the furniture, then they close the map. Are you surprised when they bark their shins?

So why does it happen? Why do companies keep making radical changes without fully explaining how those changes will benefit their customers?

Again, we can turn to Guerville for an answer, in the form of an elegant little chart

Not only are your users sitting there, seething in resentment as they realize you’ve moved everything that gave them a sense of control over their device/service/website your team thinks they have just delivered sliced bread 2.0.

This conversation captures the tension in the attitudes:

Updating the software to the latest fashion in visual design — say flat— is certainly a high value change, right? Why wouldn’t we love an interface that was hip and chic and fresh? You silly users, you like skeumorphism? That’s so five years ago.

Looking through the IOS 7 website when trying to figure out where they had hidden search, I realized Apple can’t explain the value of the change because — like most fashion—it’s subjective. The entire OS7 site is a miasma of design-flavored techno-babble and obscure internal names for features that are never explained: “Now with Airdrop!”

And throughout they tell you over and over again that is beautiful, familiar and simple, as if to hypnotize you into submission. If it’s so simple, why am I have having such a hard time? If it’s familiar, why can’t I find settings?

There are a few real clear improvements, like easy access to my calendar from anywhere including within apps. But that isn’t covered on on the OS7 site. They are too busy telling you how hard simple is, and how beautiful OS7 is. Orwell would weep.

But in some ways, it’s the Twitter example that drives home this point the hardest. It really is hard to follow conversations on Twitter. Some of the funniest stuff on Twitter happens when people go back and forth, yet it’s easy to miss. The blue line should have been a godsend. But a search shows a mixed reaction, mostly negative.

Perhaps people don’t like the change because of a a weakness in the design metaphor. Perhaps they didn’t spend enough time hypnotizing the users that the blue line is beautiful. Or perhaps they just didn’t warn people change was coming, but it was going to be ok because now it was going to be easier to follow conversations.

Maybe they took a page out of Facebook’s playbook (the company hated at the same level as cable companies) and decided to give the users “improvements” and just wait for the screaming to pass. This is an approach that works well when users don’t have a choice of an alternative. This is an approach start-ups would love you to take.

The moment you succumb to the notion that “users just hate change,” you’ve ceased designing for your audience.

Ryan Freitas

Change is expensive, even when it’s free. Change is expensive in relearning. Change is expensive when you feel like you no longer have a choice in how you live your life. For change to be accepted, it needs to first have real value to the user. Then it must be explained clearly in the language of that person’s values. Not the designers’, not the company’s.

Rather than take on admission of failure to communicate the need and benefit of a change, too many teams decide to blame the very people who write the checks: the end users.

Also See: