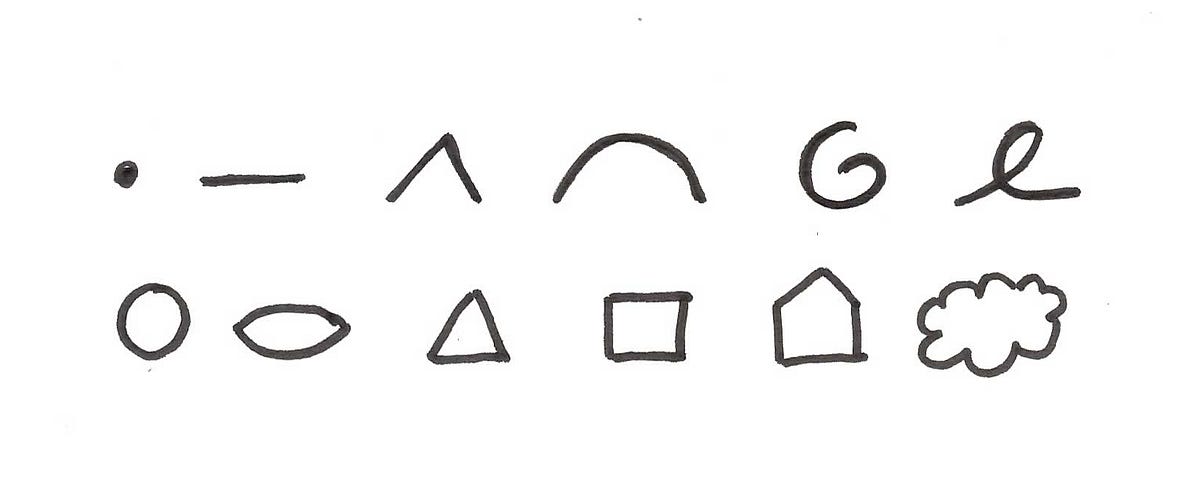

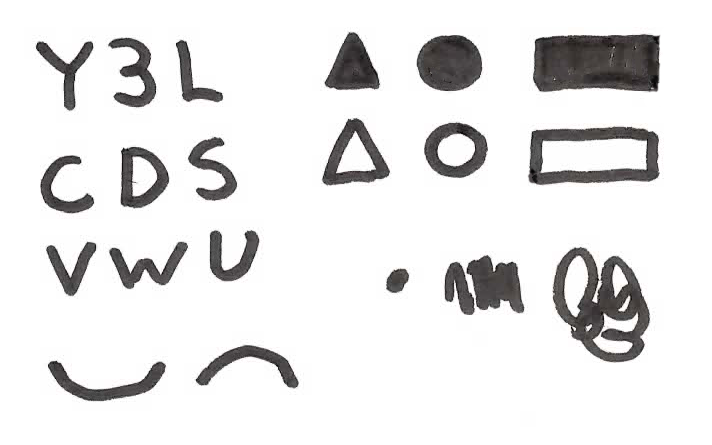

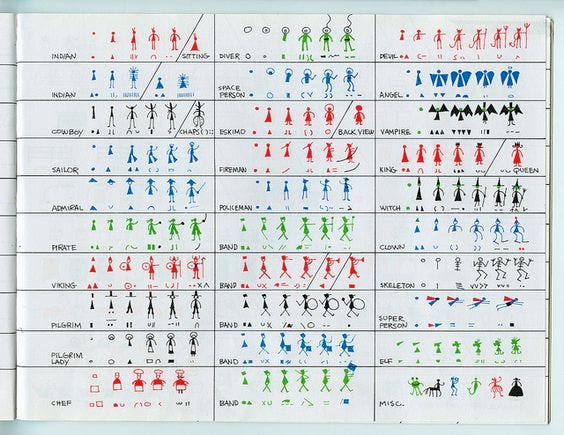

When I first got into Visual Thinking, I came across a core concept that no one agreed on: visual alphabets.

Here is the one put together by Austin Kleon, Dave Gray and Sunni Brown at a SXSW one day. I like to think it was in a bar on a cocktail napkin.

Speaking of, here is Dan Roam’s “if you can draw this” , from Back of the Napkin.

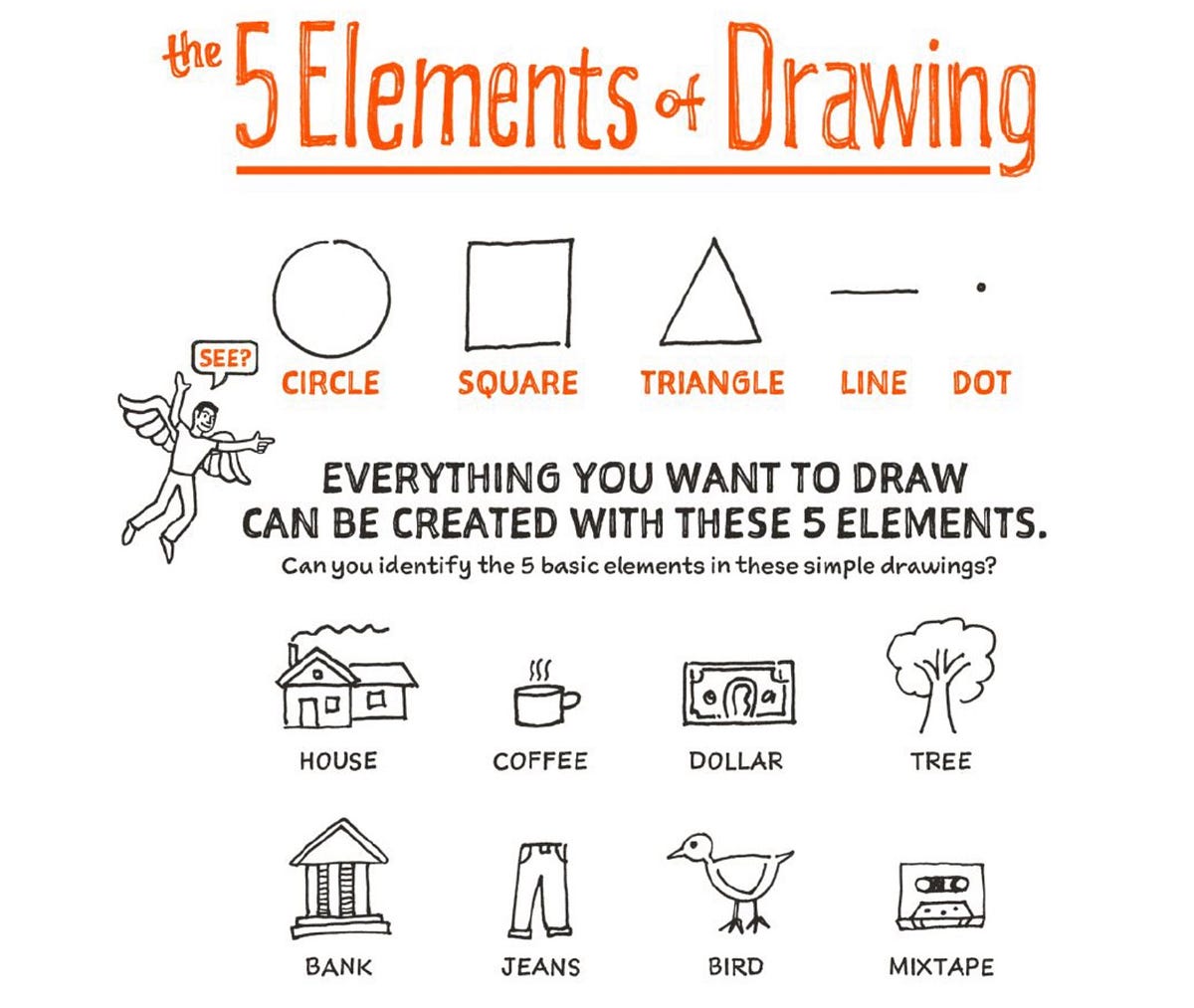

And Mike Rohde’s (of sketchnote fame) Five Elements

And from the master, Ed Emberley in Make a World: “If you can draw these shapes, you can make a world.”

I kept wondering, why are they all different? If it’s an alphabet, something basic to all doodles, why isn’t it standard? Like the roman alphabet: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ?

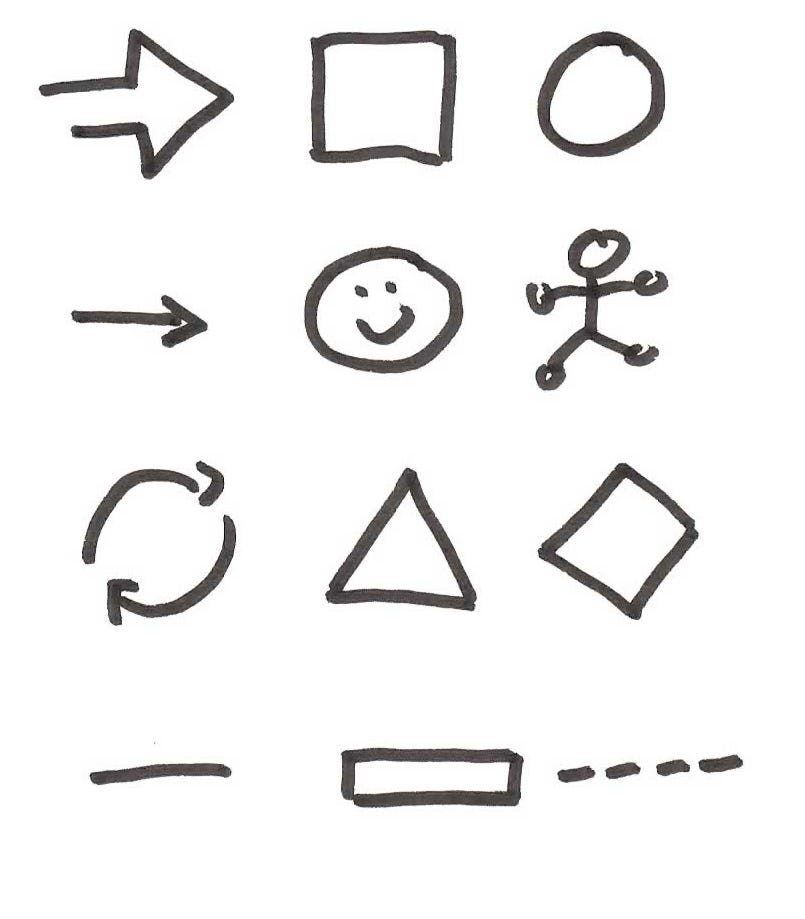

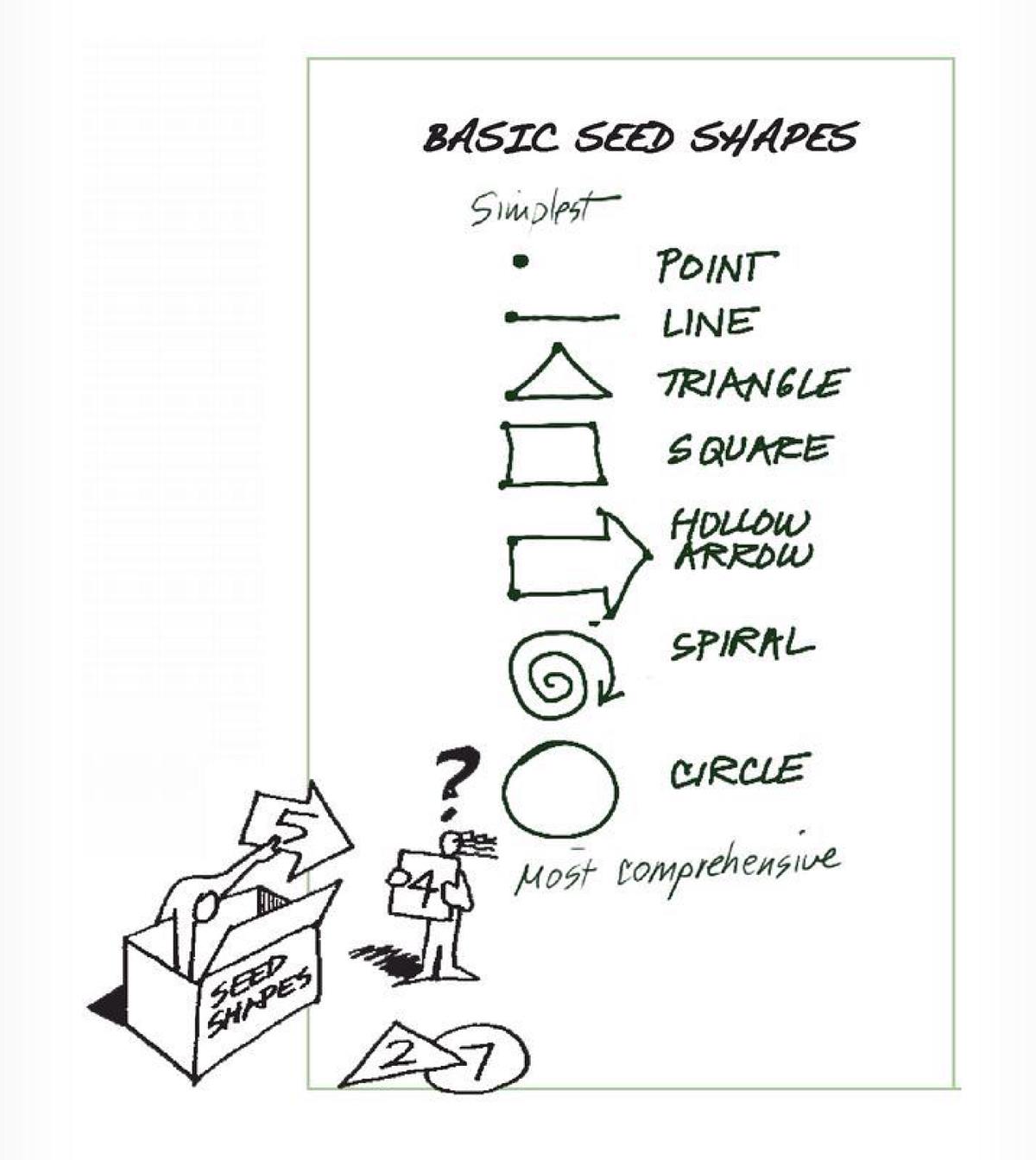

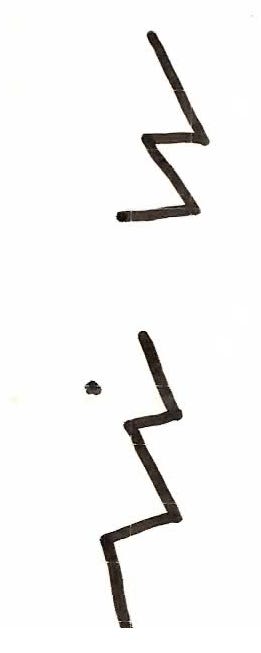

But then I came across this gem, in David Sibbet’s Visual Meetings…

Why is it a gem? It’s just more shapes, just like everyone else’s, right?

The gem is that’s just part one. He goes on to draw this:

And then I knew what to do.

It’s Just Semantics, You Say?

Alphabets, ideographs, tomaito, tomahto… isn’t this all a bunch of semantics? Let me explain why this is important by telling you about the Mayans. They invented writing in 600 BC (maybe much earlier), but when the Spanish invaded in the 1500’s, their civilizations had already collapsed, and they were living in small villages.

The villagers had held on to a treasure: dozens of books written on fig bark that held their history and culture. Spanish priest Diego De Landa burned these to encourage the Mayans to convert, and managed to stamp out their ability to read their own language. Or anyone else’s.

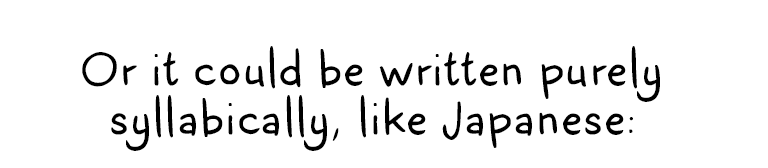

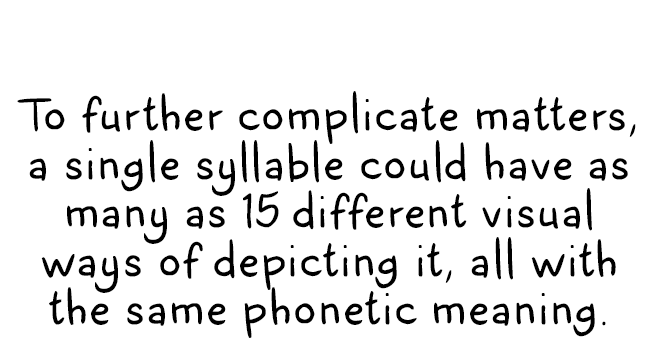

But what matters for our interests is that no one could decipher the writing because it was a weird size- it had more characters than it should have. Most writing systems are alphabets, syllabaries or logographies. Alphabets are small, because a symbol is a phoneme (sound.) Syllabaries are slightly larger — imagine if c, h and ch were all separate symbols. And logographies are the biggest because there is a separate symbol for every word, both ideographs and pictographs.

But Mayan had vast amounts of characters, sometimes drawn stand-alone and sometimes combined into new characters, and their writing didn’t match what anyone knew about any writing system.

The Mayan writing system was slowly deciphered bit by bit by a string of people, including a Russian linguist, an art historian, and a child of archaeologists who grew up in the ruins surrounded by Mayans who taught him the spoken language. He published his first paper at 12. That’s not relevant to my figuring out what visual thinking really is made of, but it’s pretty cool. Tell your kids to stop playing video games and climb a pyramid occasionally, dammit.

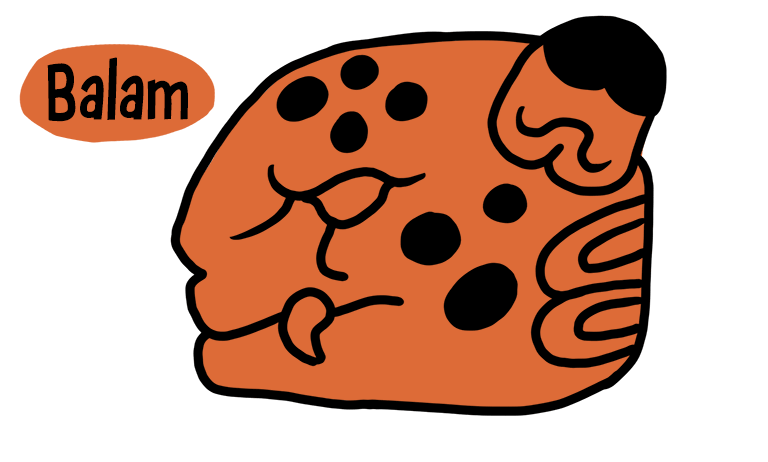

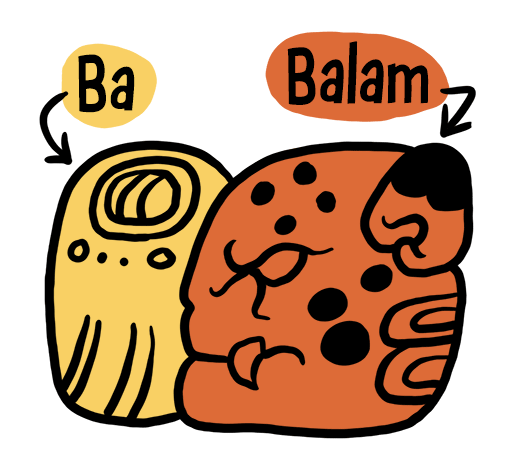

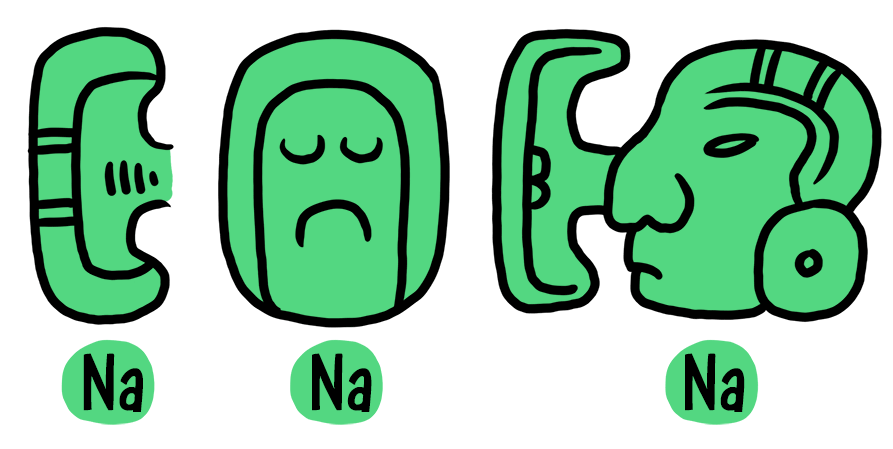

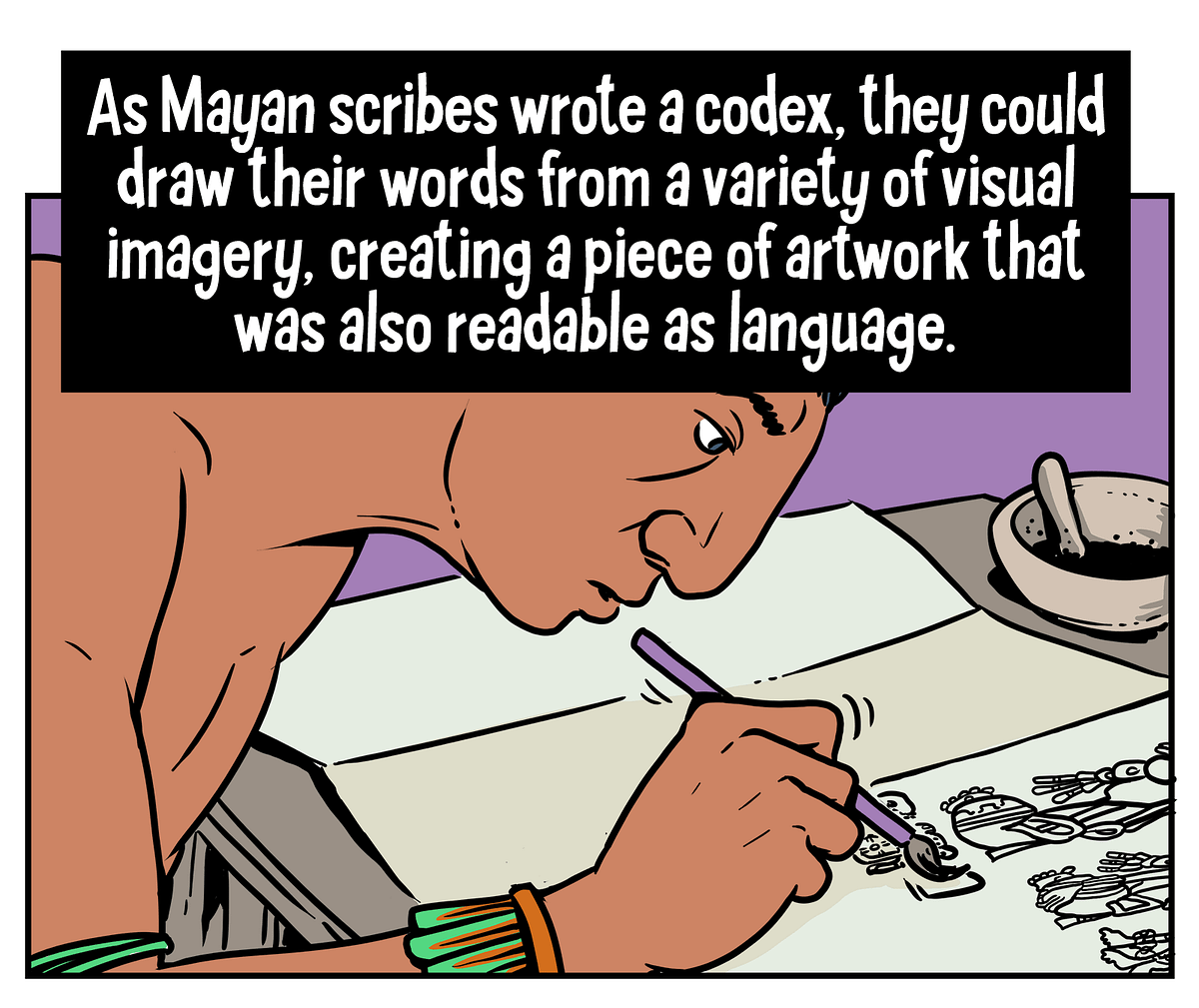

Anyhow, here is what David Stuart figured out (images blatantly borrowed from Andy Warner’s comic, GO READ IT!)

Again, all these awesome images from Andy Warner’s comic, GO READ IT!

Want to be an awesome visual thinker: Be Mayan!

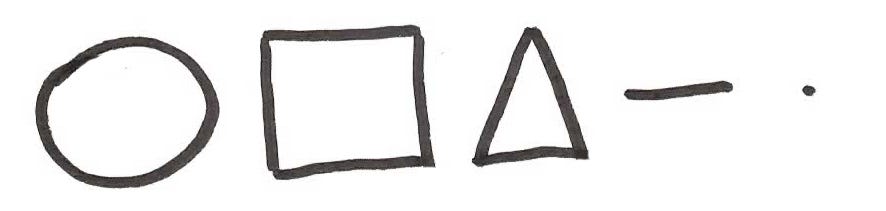

Artistic license is the secret! You have to make your own language! It’s not about shapes! That’s like saying you can learn to write English by drawing lines and circles! (Ok, drawing lines and circles helps you write neatly.)

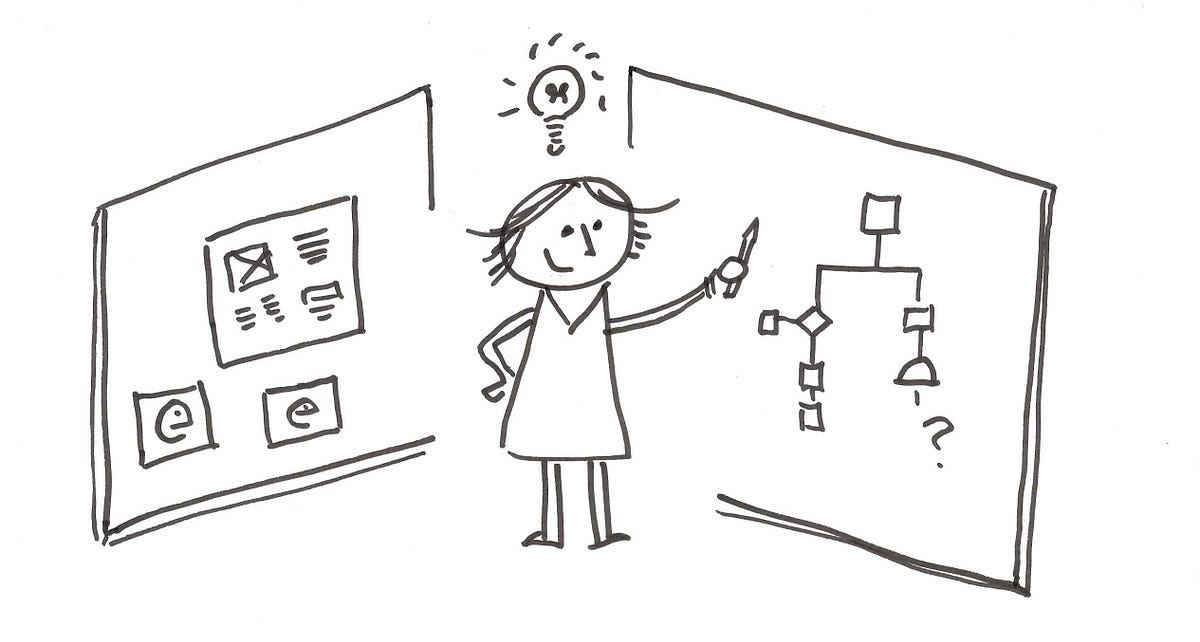

If you want to do Visual Thinking — from sketchnotes to graphic facilitation to whiteboarding with teams — you need to build a visual vocabulary of how you, the person with the pen, will express your pictographs and ideographs.

If you want to do Visual Thinking — from sketchnotes to graphic facilitation to whiteboarding with teams — you need to build a visual vocabulary of how you, the person with the pen, will express your pictographs and ideographs.

Your job is to determine how you render core ideas like “user” “idea” “database” “struggle” and any other things you need to draw.

There is no visual alphabet, but there is a visual vocabulary. (0r– nerd alert!– a logography)

You can invent it or you can steal it, but you need that vocabulary if you want to say anything with pictures.

Shapes help you build the vocabulary, like practicing circles helps you make a good looking Q, but they are so NOT ENOUGH.

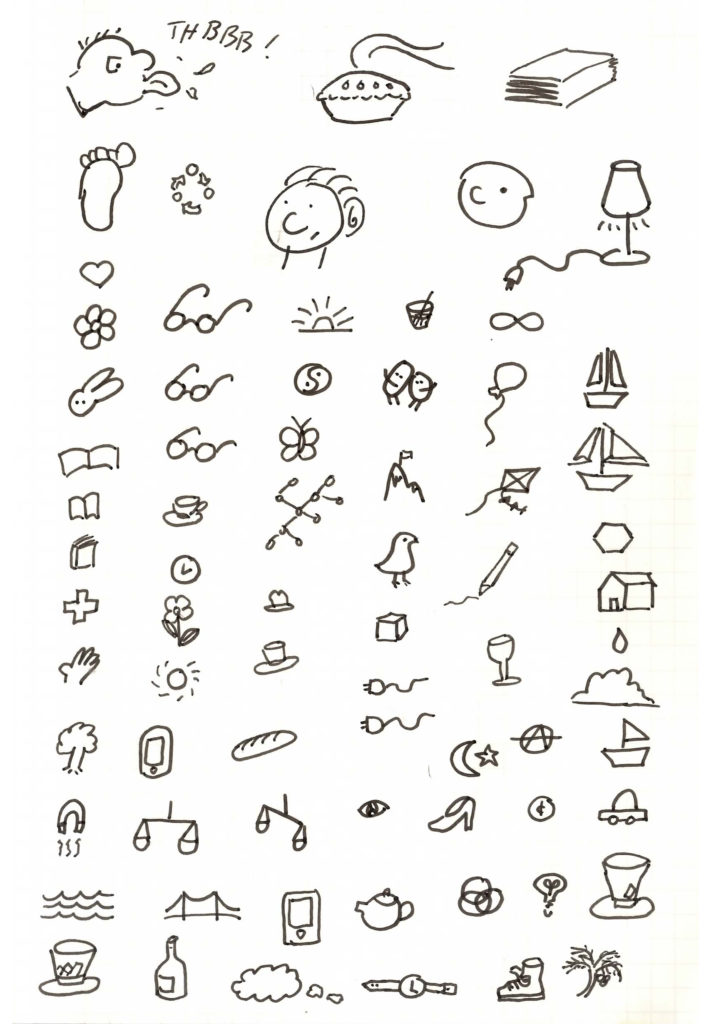

What You NEED to do is build a vocabulary of the things you need to say. Drawing shapes is good for manual dexterity (like learning to make the french “rrrrr” sound) BUT if you want to be articulate, you have to build a vocabulary. By drawing LOTS of stuff.

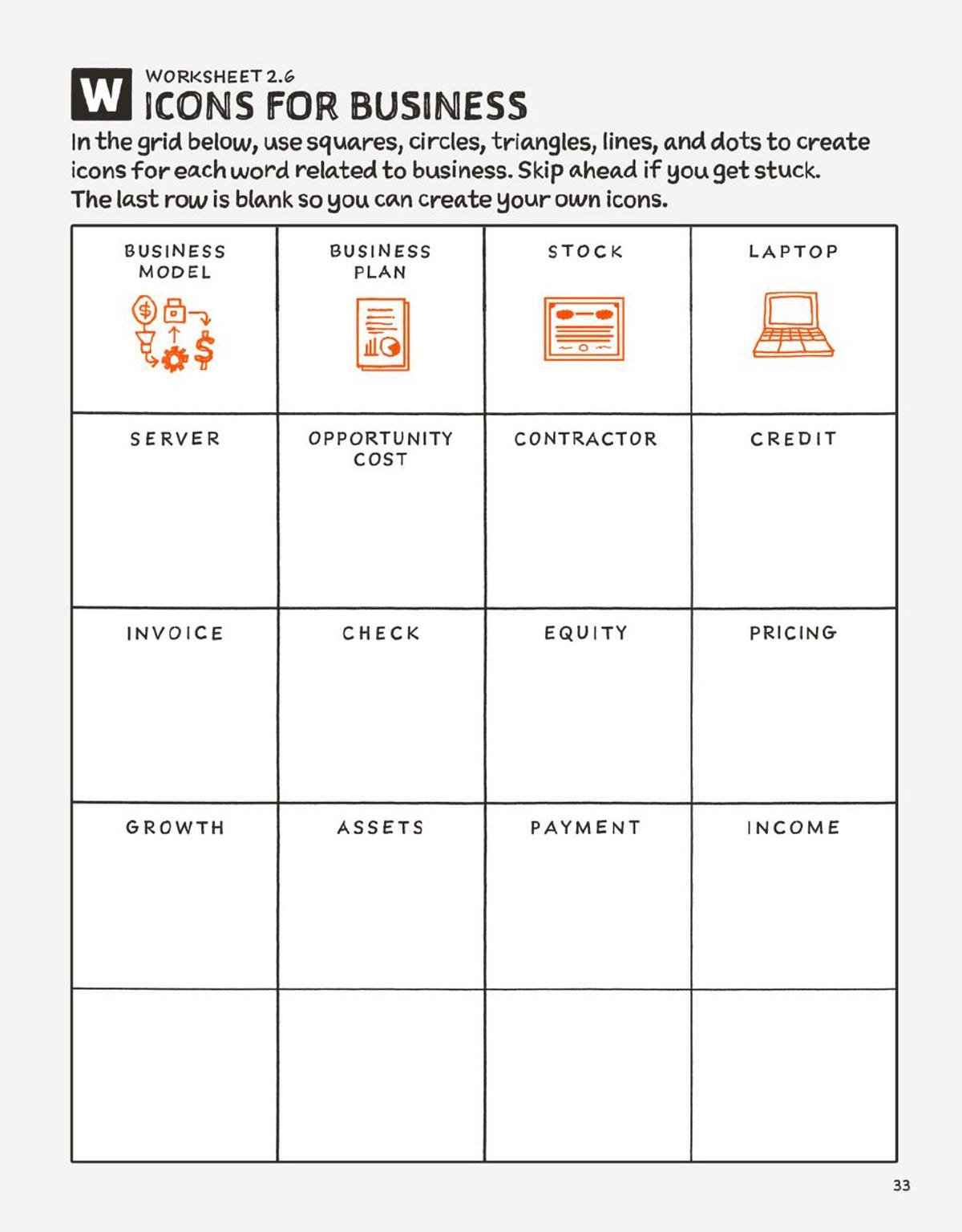

Rohde has these nifty worksheets in his Sketchnote Workbook, and you should probably make some for your field.

Let’s invent a writing system! Who’s with me?

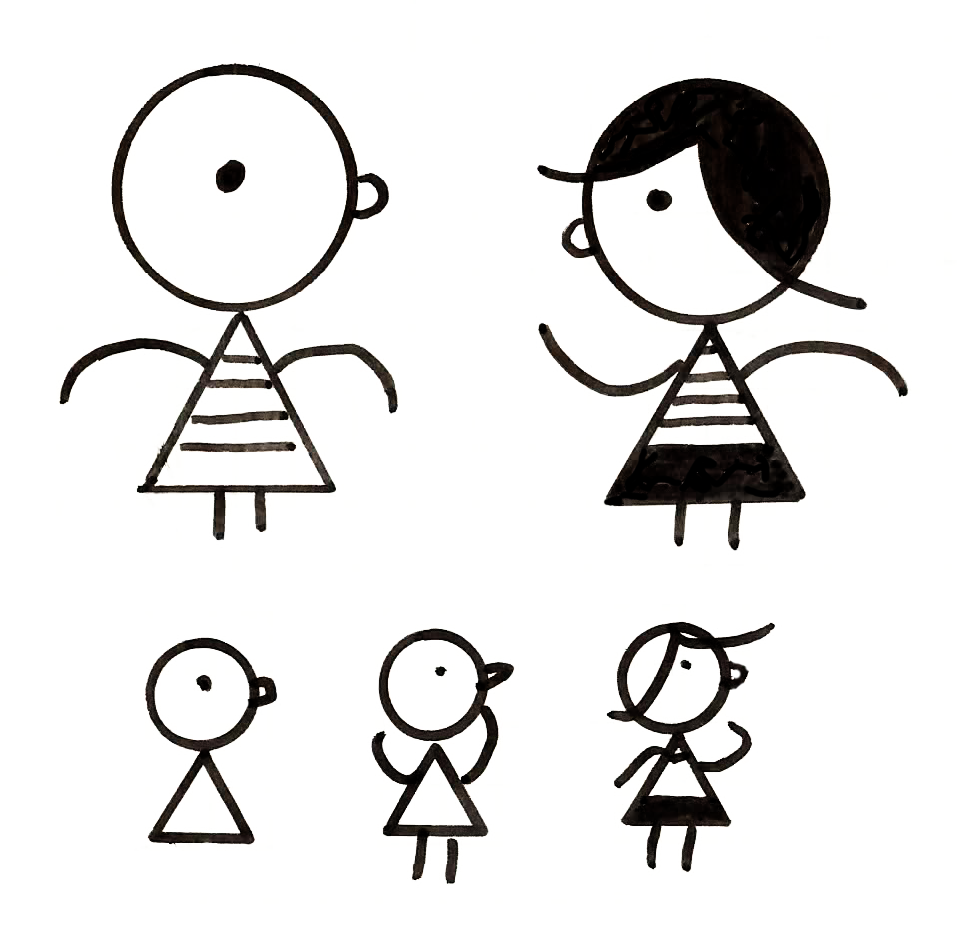

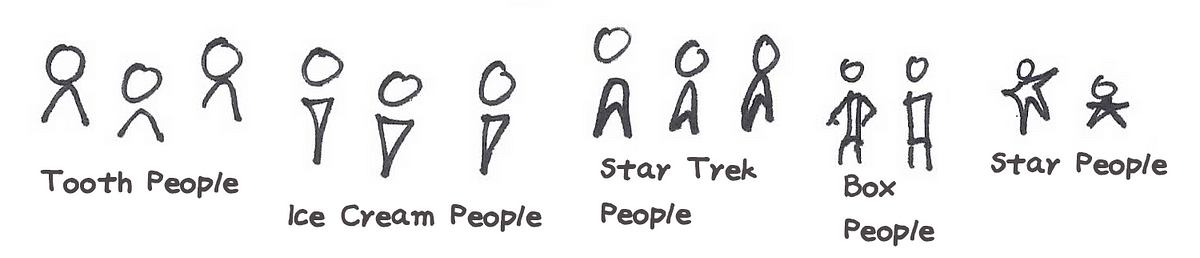

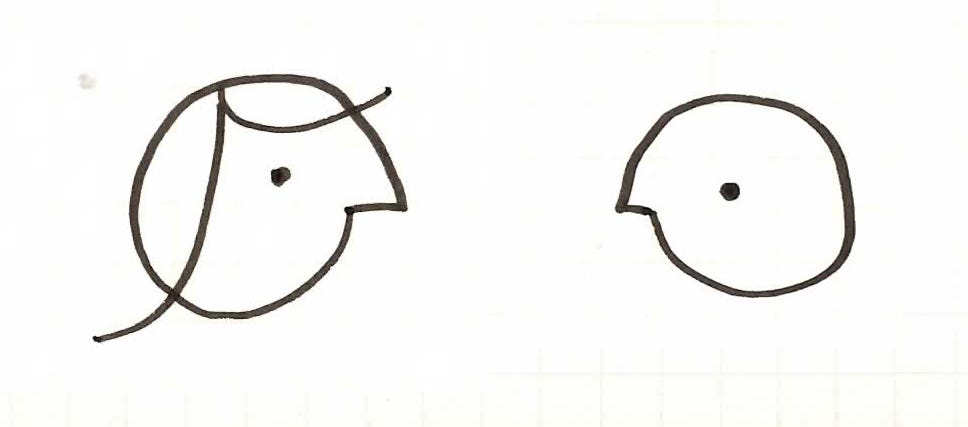

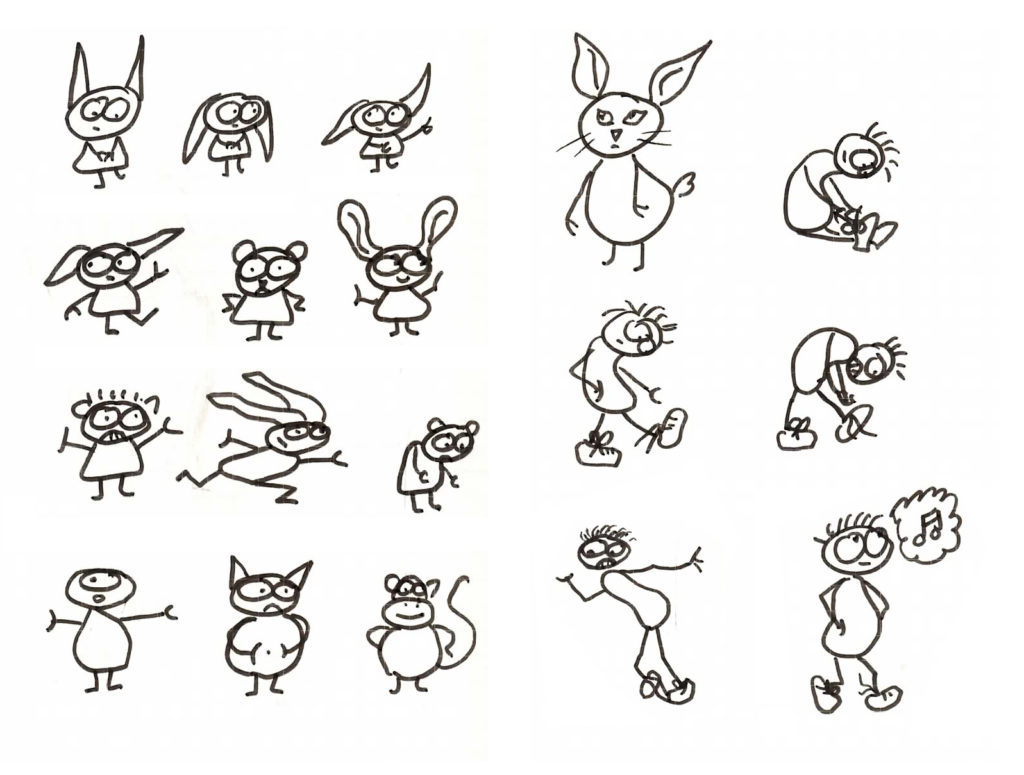

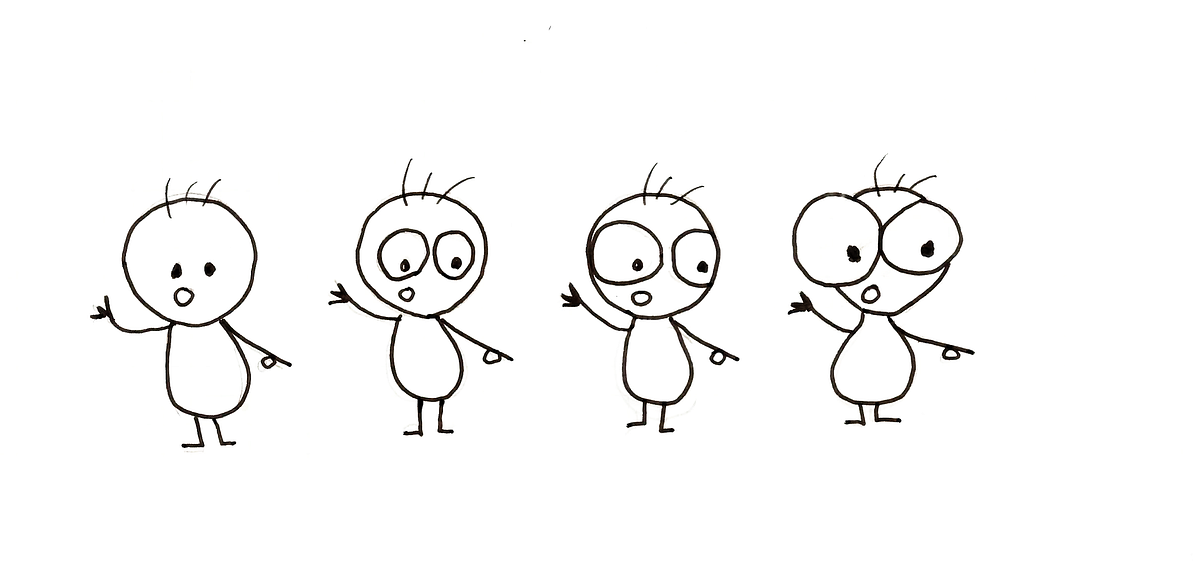

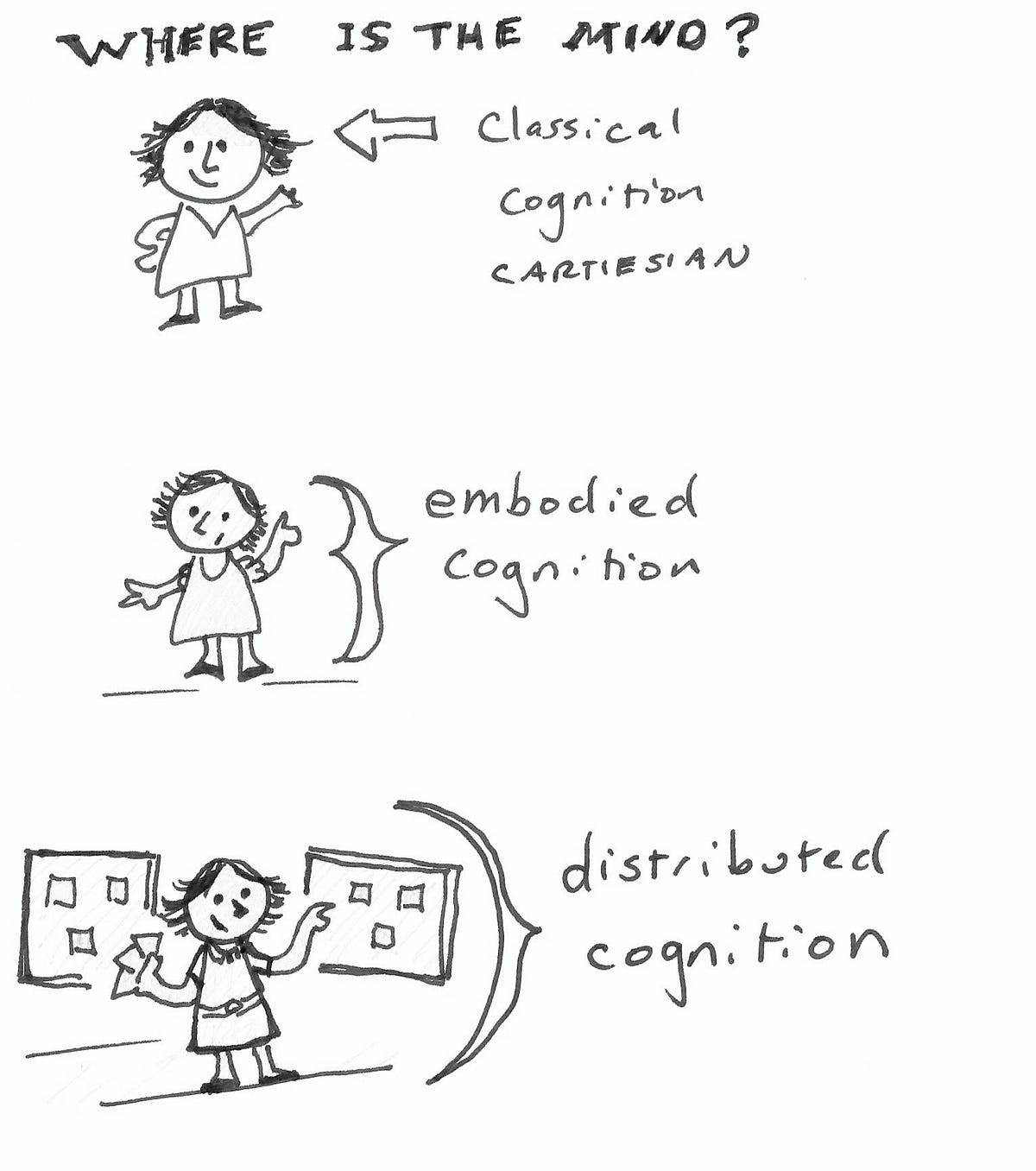

For example, I had to figure out how I say “person,” i.e. when I get up in front of a whiteboard, what do I drew? What’s comfortable and looks good? What’s fast, and I don’t have to think about?

There are a lot of ways to draw people far away. These are useful for drawing crowds.

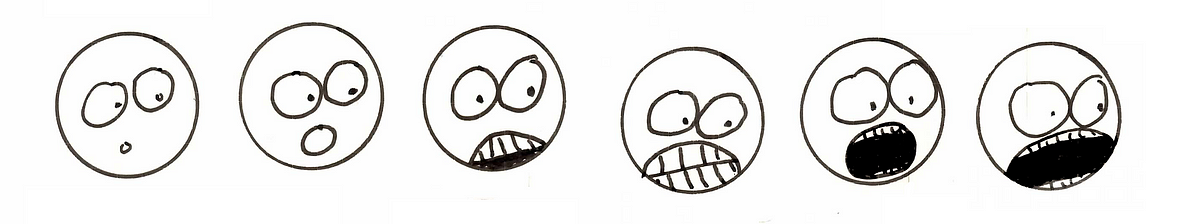

For faces, one can consider Hugh Dubberly or Bill Verplank draws them….

With Verplank, lighting becomes a face….

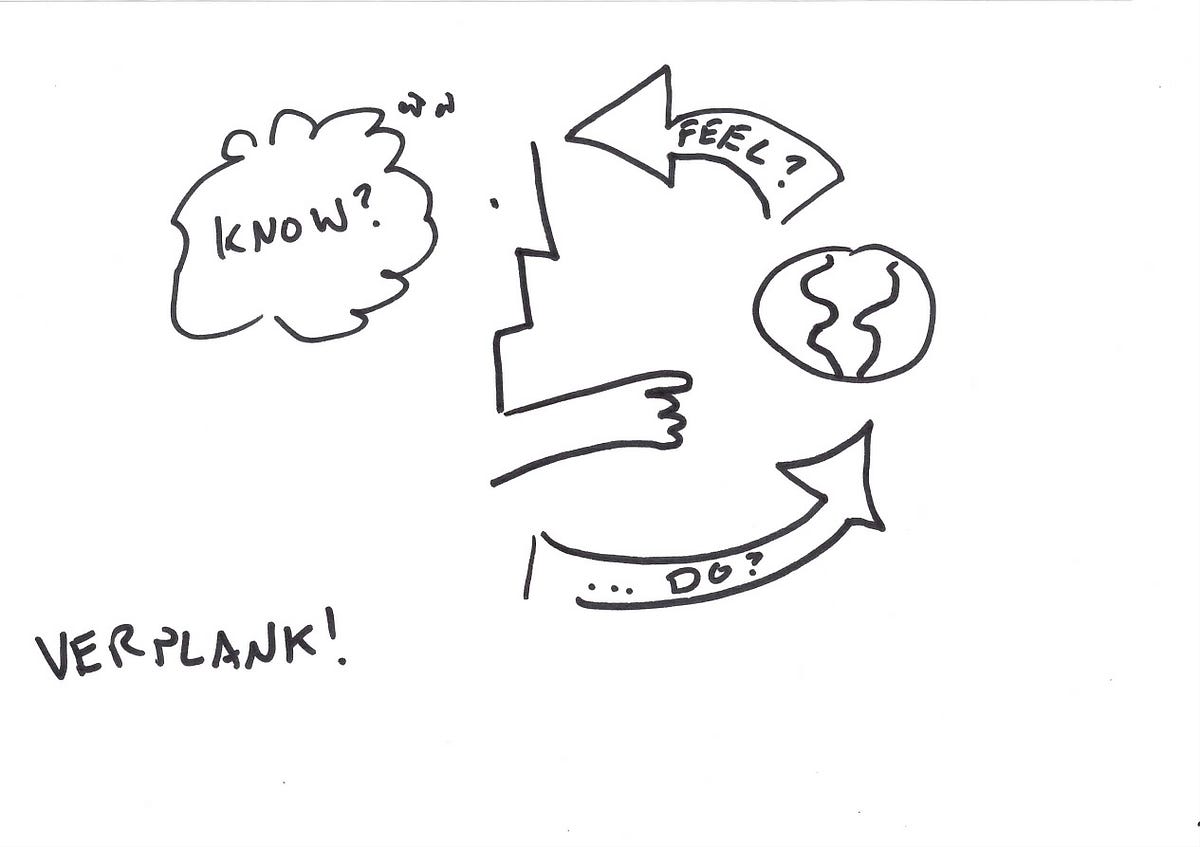

As in this famous diagram

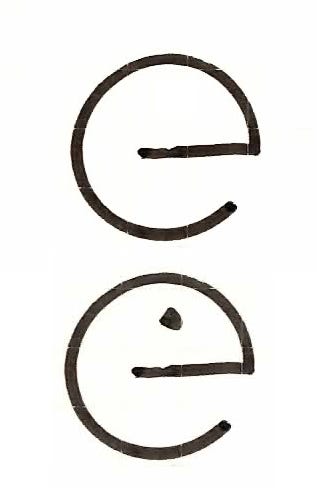

With Dubberly, faces are based from the letter “e.” This is super convenient. It works because of pareidolia. Look it up, it’s a thing.

After all that, I ended up with deciding this is how I draw faces:

Which I use a lot, including when drawing an empathy map or my modified Value proposition canvas on a whiteboard.

And what about the most common use, medium distance? Brunetti or Gray?

So many possibilities!

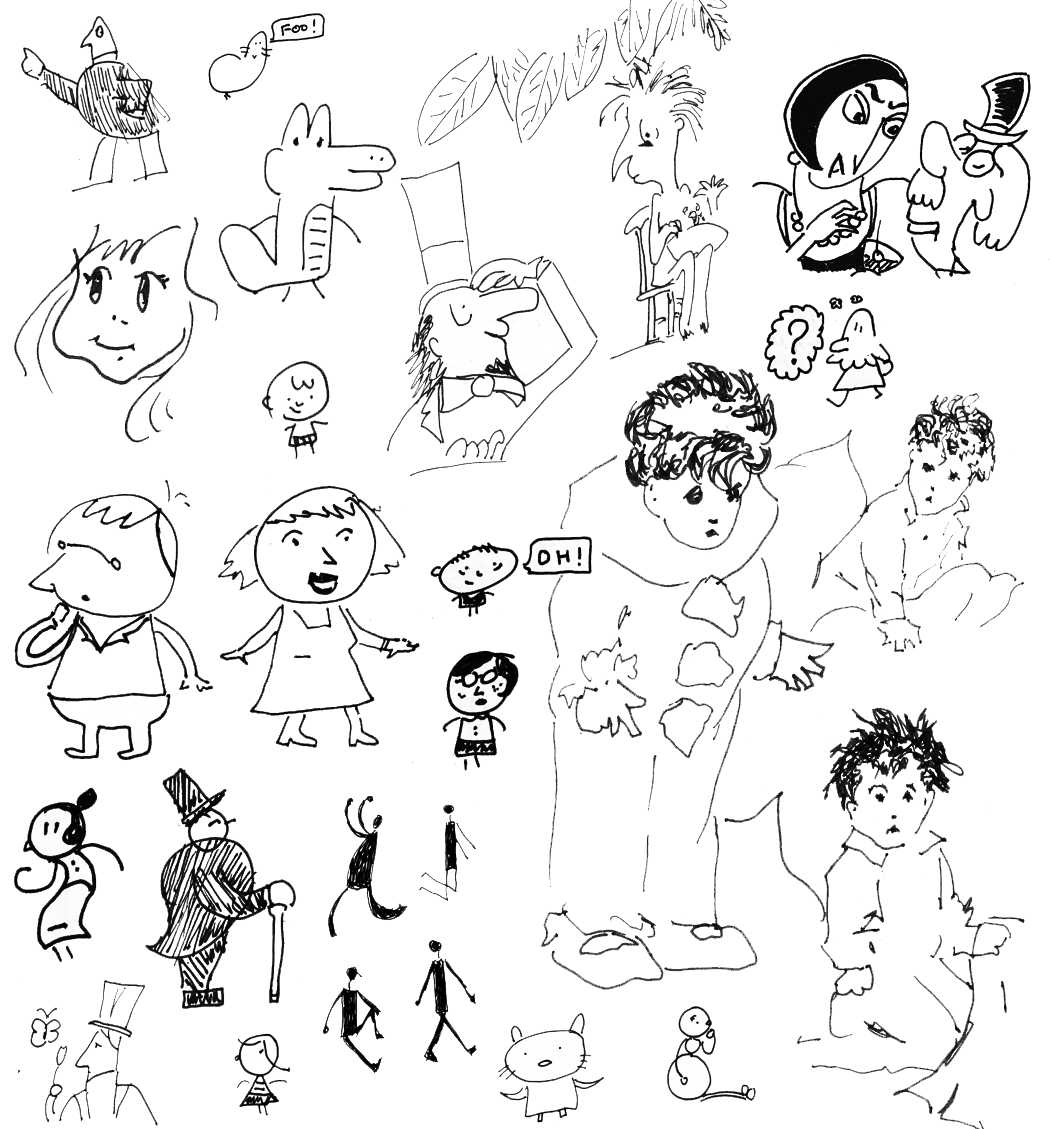

I found exploring my own personal visual language was a lot like being a cartoonist, and finding my style. I copied a lot of people

and played with things I liked

I messed with proportions

and slowly built a vocabulary to express ideas.

Eventually I realized that it’s fun to have a style for expressing complex ideas

or even just joking around

But for working, like whiteboarding apps and ideas, simpler was better. I wanted speed and the ability to concentrate on the problem I was solving. Thus I needed to make sure the imagery was as unconscious are writing the words.

I had traveled around the drawing world, and came back to Ed Emberley. His simple drawings made of simple shapes (Oh! Shapes….) is the easiest way to say anything.

Drawing simply like a kid is quite ok. I have a BIG vocabulary now. If need to say something, whether it’s on an index card, a whiteboard or in my sketchbook I have a way. If Iwant to make a joke, create a concept model, or a quick flow chart with an actual user in it, I can do it. I can express my ideas so I can see them, evaluate them and communicate them. I can talk to others, or just talk to myself.

Anywhere, anytime, I’m ready. I’m Wodtke literate.

If you made it to the end if this huge essay, it’s time for you to invent your language!