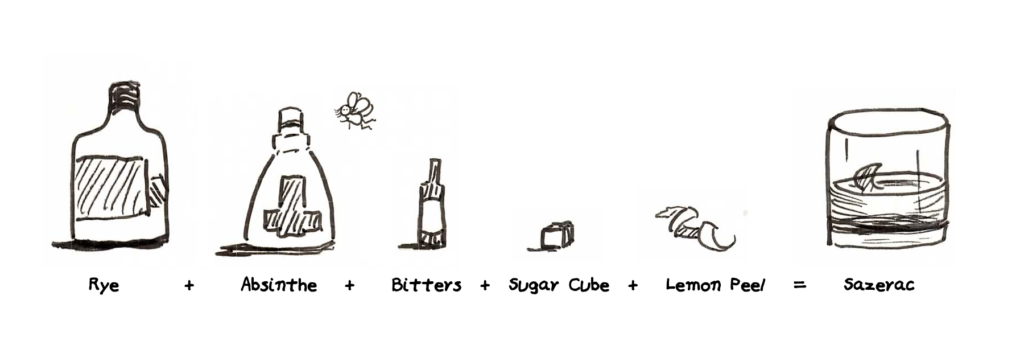

I was enjoying a sazerac with a old friend of mine at a local watering hole. And by watering hole, I mean incredibly hip farm-to-table restaurant full of young techies because we were in Mountain View, land of Google, but hey, we were sitting at the bar. I can pretend I’m in New Orleans.

She began to tell me her ideas for a new talk she was developing for an upcoming conference. She bounced around from idea to idea, peppering it with facts and stories jumbled together, then paused for feedback. I emptied my glass, and asked her, “What’s your thesis sentence?”

She stared at me like a middle schooler who’d just been called upon by the teacher.

“I’m going to visit the ladies. You can tell me when I’m back.” (I’m not usually this rude. I blame the absinthe.)

Most talks are twenty to forty-five minutes long. If you are a speaker, that sounds like an eternity. But in reality, it’s a tiny amount of time, especially if you want to communicate a nuanced idea. Also consider that most people only listen at 25% efficiency (and that’s without a Pokemon Go stop near the conference room.) All talks suffer from the conundrum of a speaker who always wants to communicate a huge amount of information, and an audience who is catching about a fourth of it. What can you do?

Say Less, Better.

Before you start work on your talk, imagine this. It’s right after your talk at the break. You walk up to an attendee (in disguise) and ask, “Hey did you catch that last talk? What was it about?”

What do they say?

Their answer is your thesis sentence. It should be is the one big idea you want them to walk away with. And it’s great if they expound on that idea with your supporting facts, if they can retell a particularly charming story you shared. But that’s not as important as making sure they get the one big idea.

Imagine you walk up to them, ask, “what was that last talk about?”and they respond, “I dunno, something about coding.”

Ouch!

It’s critical is you pick a single message to impart, then hammer on it over and over.

“Your number-one mission as a speaker is to take something that matters deeply to you and to rebuild it inside the minds of your listeners. We’ll call that something an idea.”

― Chris J. Anderson, TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking

Let’s look at the top ten TED talks. Here what I think the thesis statement is for…

Do School Kill Creativity?

Thesis: Our school systems are incapable of supporting creative people, which is a critical skill in modern times.

Your body language shapes who you are

Thesis: You can change how you think and feel by changing your body’s posture.

How great leaders inspire action

Thesis: Successful companies have leaders who don’t tell customers what they do, they tell customers their meaningful mission, and that’s what the customers want to buy.

The power of vulnerability

Thesis: We think it’s important to have all the answers and be strong, but actually we connect more deeply with other and are more successful in life when we are open about our vulnerability.

All are ideas worth spreading!

Now you try it: go through the next few talks, and I’ll bet they all have one simple message, and spend the rest of their 19 minutes proving it matters.

When I was writing my first book, I would get completely tangled up in all information I wanted to convey. I’d be writing in convoluted circles, lost in the jungle of words. I eventually had to stop, and before writing the next paragraph, ask myself “What am I trying to say?”

Somedays it was so bad, I had to ask myself, “what am I trying to say” before writing each sentence. If I asked, WAITTS before starting the next chapter, the paragraphs and sentences came easier. Eventually I wrote “WAITTS” on a post-it and stuck it on my monitor.

I waitts, then I writes.

I have changed from throwing myself at the page and hoping for the best to pausing regularly to order my thoughts before committing them. Crafting that clear concise thesis sentence made all the difference. It’s the same for creating a talk.

In case you were wondering: I came back from the restroom to a fresh sazerac.

“Oh, this will never end well,” I hoped aloud.

“I’ve got it!” my pal gushed, her fresh drink a bit lower already. “Lean Start-up is a force multiplier for teams already working with Agile …” yadda, yadda, yadda….

I took a sip of the sazerac. I thought I knew what she meant, but I wasn’t sure. Then I realized if I wasn’t sure, would the audience be?

“What do you mean by ‘force multiplier’?” I asked, and then continued to ask her to explain each of her ideas.

She then paused, thinking, and took another sip of her drink. “How about instead, ‘If you are Agile, you’re almost Lean?’”

I asked, “Are you sure everyone in your audience has the same idea of Agile? Or Lean?”

Most audiences share the same language, but more often than not they don’t know all the words in that language. In my experience, there is often someone from a different country, like France or Japan or Missouri who has a different idea of how a method is implemented, or has never heard of the term you’ve been using forever.

It costs you little to use plain english, or to briefly explain a term. You can even cheat a bit, saying something like “As well all know, Lean is all about quickly moving through cycle of the building small experiments, measuring results, and learning what works.” Ok, we all know that NOW.

Next I asked my friend, “Why is that idea important?”

A good thesis sentence both explains the idea and why it matters. I’ve sat through way too many talks that consist of “Fact! Fact fact fact! Fact!” and I am left going, “o-kay… now what?”

Make sure your thesis sentence has the big idea AND why your audience should care about it. What obvious to you is rarely obvious to your audience. Spell it out.

She eventually came up with something like, “It’s not enough to build software quickly using best practices, it needs to be the software that customers want so the business can succeed.” (paraphrasing, second sazerac, remember?)

It’s a bit long, but not too long to be explained and expanded upon in a 45 minute talk. As well, it uses simple language you are sure everyone in your audience will understand.

Simple language does not reflect a simple mind. You don’t have to use jargon to be impressive. It’s better to have a great idea you can express in language anyone can understand. Great ideas deserve to be understood by everyone.

Now you are ready to design your talk. I plan to write another essay on techniques for talk creation, but for now the tl;dr is

Every story, fact and insight in your talk must tie back to your thesis. If it doesn’t throw it out.

Kill your darlings.

That fun fact that has nothing to do with your thesis? Ditch it. That charming opening story that has nothing to do with your thesis? Toss it.

I went through this with my talk, Radical Focus. Originally I opened with a Zen story that was really charming but had nothing to do with my key lesson. Man, I loved that story. But one day I sucked it up and replaced it with the Greek myth of Atalanta, whose moral perfectly matched my message.

When you are tired of saying it, people are starting to hear it.

-Jeff Weiner

It may seem tiresome to repeat yourself. But what is old to you is new to your audience. Repeat that thesis over and over. Do it in different ways, to keep it fresh and interesting. Use a fact, an anecdote, a myth. But repeat.

The entire point of a talk is to impart an idea you care about enough to get on stage in front of hundreds of people — which is terrifying.

Don’t you want them to remember what you said?

You may also want to read:

In Praise of Q&A

Beyond the Slide

The Secret to a Great Presentation