This is a write-up of a key learning from my fall class “The Creative Founder,” open to Juniors and Seniors at CCA. It was mostly attended by Interaction Designers, but had some industrial and graphic designers.

Want to take it? I teach an abbreviated version at Stanford Continuing Studies this spring.

In my Creative Founder class, students work in a small team all semester, trying to create a viable business. Until my class, the longest they’d had to work with another student had been about three weeks. If they were annoyed by a teammate, or if someone didn’t pull their weight, or if someone had dreadful communication skills, they could simply wait it out and that person would go away. Then they just had to avoid working with that person again.

Unfortunately, this is not a strategy that lends itself well to real life.

At the eight week mark — about halfway through the class — the students were all struggling with issues with one or more more of their teammates. Is that person not pulling her weight, is that person a bully, is that person checked out…? Moreover, halfway is when you have profound doubt about the business itself. Did we choose wisely? Is there time to pivot? To what? How much data is enough data?

In the middle of the dark night of the soul, I hold a class about effective feedback. This year a student jokingly called it “empathy day.” I feel good about that; it means I may have finally figured out how to teach feedback correctly.

Feedback is a word that strikes terror into many people’s hearts.

“Feedback” is often used to mean “I’m going to tell you what’s wrong with you.” I used to be terrified of feedback, because all I heard was “you are a bad person.”

Over the years I’ve studied feedback: to to give it, how to take it, and how to use it to live in a state of constant growth. It still scares me a little, but I value it because it makes me more effective.

Feedback helps you see yourself as others see you.

More importantly — when done right — it can make you feel seen. When someone notices something you do and expresses appreciation or offers coaching, it can make a profound connection. A team that provides each other feedback for the purpose of growth is a team that succeeds together.

Team feedback has two parts: the group level and the member level. A team has to look at each member and their contributions AND how the individuals come together and work as a unit. If you only give individual feedback and never examine group dynamics, you’ve only god half the puzzle.

In the Creative Founder class, we start with the team.

It’s easier to begin with team feedback because we all share responsibility for the team’s performance, and thus all share blame.

As prework, I had students fill out two things.

- A Team Assessment. I modified it from Stanford’s Interpersonal Dynamics class.

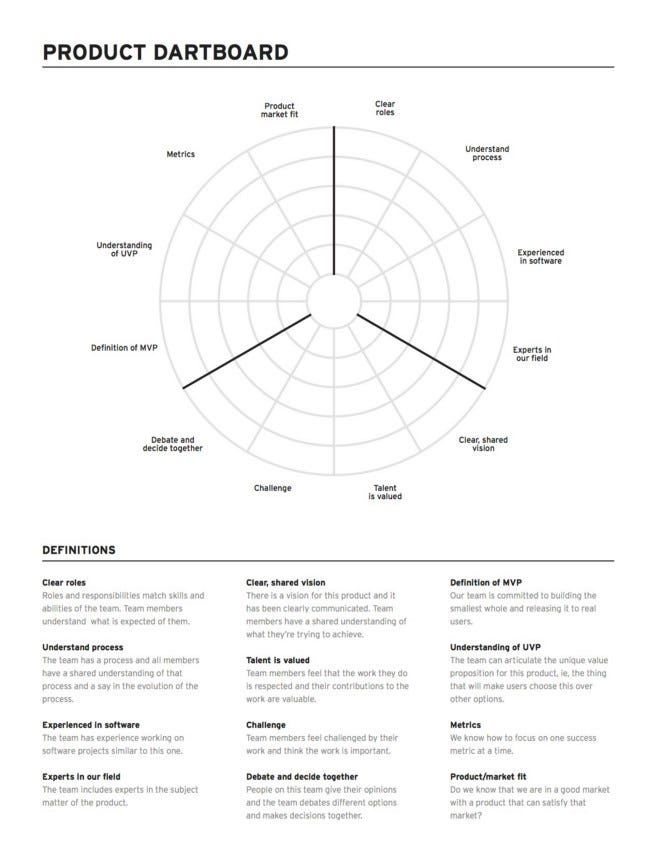

- The Carbon Five Product Dartboard. One of my students had sent it to me suggesting we try it. I liked both it and having student input into our process.

Feedback Day

We started the day with a Nonviolent Communication exercise called “Sometimes I….”

We started the day with a Nonviolent Communication exercise called “Sometimes I….”In this exercise, you place two chairs next to each other, facing the opposite way. It’s like sitting in a car together, except one person is facing backward. We all know the best conversations happen on road trips, right?

In the exercise, you take turns finishing a sentence that starts with “Sometimes I…” One person talks for three minutes, only finishing that sentence, and the other listens silently.

You can be silly “Sometimes I pretend to be supergirl” or serious “Sometimes I pretend I know what I’m doing.”

Then you switch, but with a new sentence.

- Sometimes I pretend…

- Sometimes I wish…

- Sometimes I’m afraid…

This is a powerful empathy building exercise.

It’s hard to describe how magical it is. Because you are not looking at each others eyes, you are free to confess. Because you are being listened to, you feel cared for. And hearing someone be silly, be brave, be vulnerable, released from the pressure of having to respond, is intimate and precious.

Each person spoke to each member of their team, and listened to each.

Elissa’s blog post captures the experience:

We had sentence starters such as “I wish people..” “Sometimes I pretend…” “I worry about…” “I hope…” which got personal pretty quickly after we all ran out of general hopes and wishes. I felt uncomfortable and vulnerable talking about these things with people who aren’t my mom or best friend. I did feel closer after listening to my group’s responses, it made me know them deeper and feel more personally connected to them. I felt happy to be closer to the people that I work with so closely. We see each other for 6–9 hours a week or more, yet I realized I barely know anything about them.

It’s difficult to share who you are, yet it also connects you in a way ordinary communication, such as

“Hi Bob”

“Hi Joe! How’s things?”

“Fine. How’s things with you?”

“Fine!”

…can never do.

Team Feedback

Next the students compared the answers to the prework, and discussed their findings.

They looked at where they felt they could grow, where they were succeeding, and where people disagreed in the assessments. The places you disagree are the best places to learn.

Why does one person think communication is great, and another person think it’s awesome? Do people have different needs? Are different people being supported in different ways? A group is complex, and you have to cautious navigate expectations and outcomes.

The Dartboard helped clarify places of conflict.

Are we talking about the same product when we sit in that conference room? Do we know what our roles are? Are we getting closer or further away from our goals and a clear understanding of what we came here to do? — Noam

They had created team charters — rules and norms for team behavior — at the beginning of the class. Using the assessments they did, they revised the charters.

Member Feedback

Next we worked on team member feedback. I had tried a technique last year that worked extremely well, and I used it again with a slight modification.

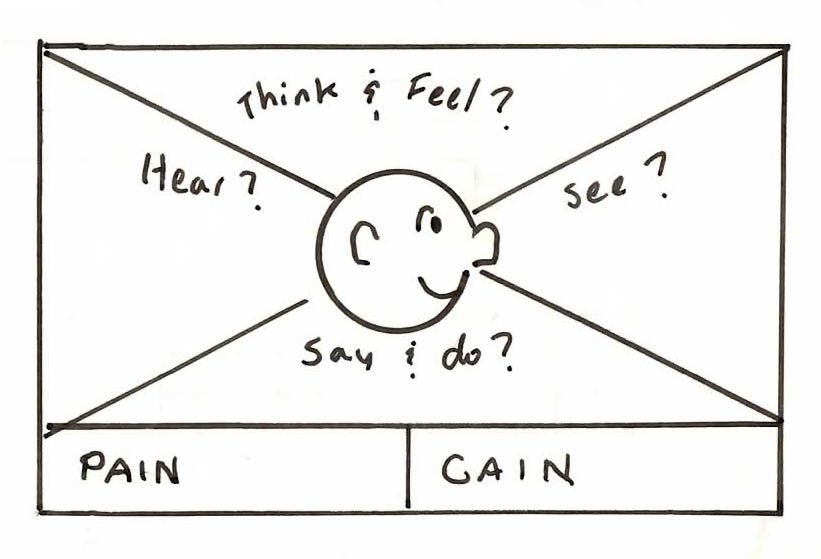

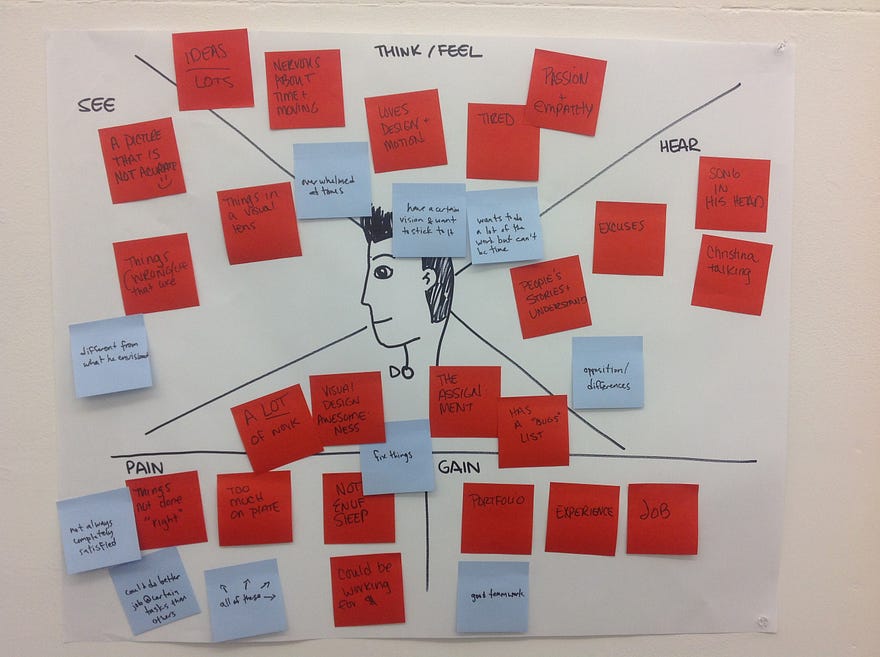

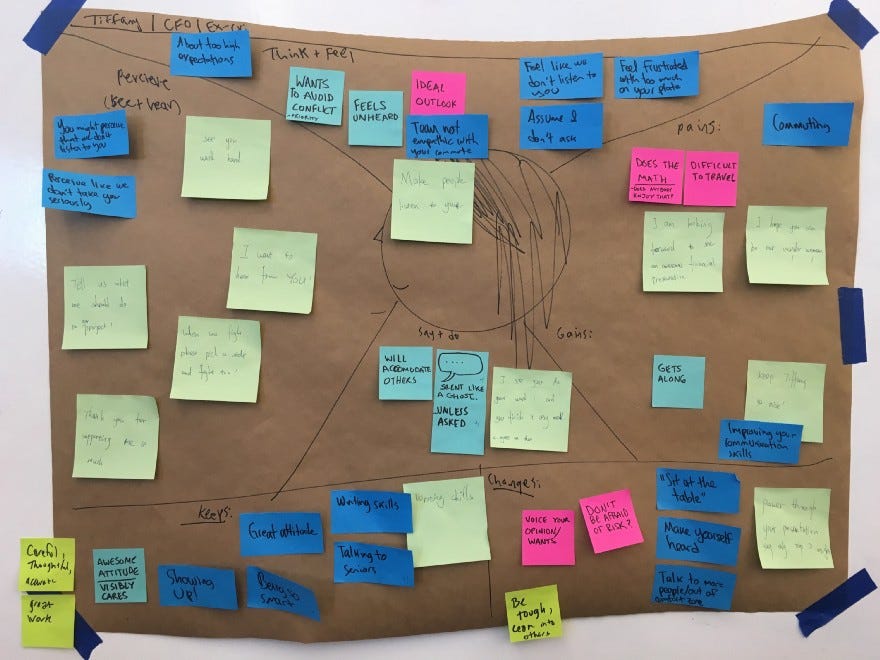

Last year we started with Dave Gray’s Empathy Map. Students drew one of themselves in the middle, then each teammate had five minutes to try to fill in all of it with post-its.

Last year it looked a bit like this

Which was a pure act of empathy. Each student got to feel seen.

This year I modified it a bit. I combined hear & see, moved pains and gains to make room for keeps and changes. So it was empathy AND feedback.

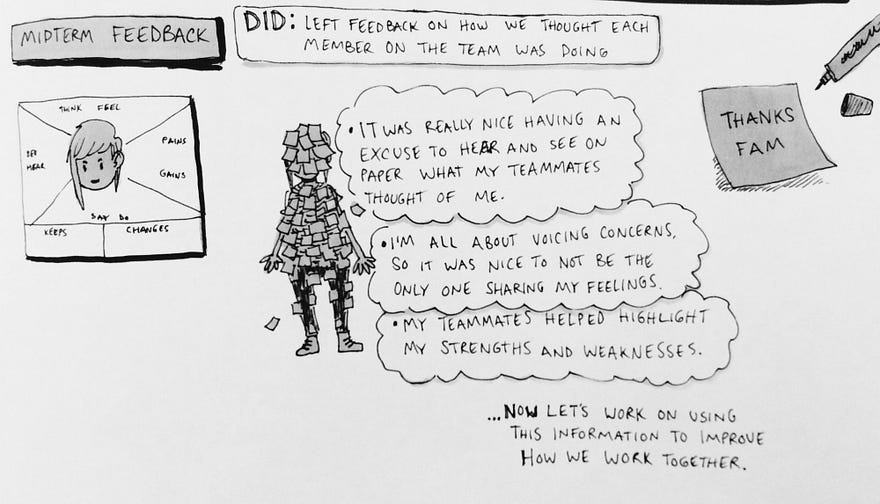

You can see it in my student Jherin’s sketchnote.

Just doing an empathy map was already emotionally dicey. Last year my student Annalisa wrote a poignant post on what it felt like to realize everyone on her team was conscious that she was the only woman.

Adding Keeps and Changes meant you weren’t just empathizing, you were offering feedback. This raised the stakes.

What I like about the empathy map is it keeps students in the realm of behavior, and out of the world of speculation. “I see you not showing up on time,” rather than “you don’t care about the team.” In later classes we further explored feedback formats, such as Matt Abraham’s Four I’s.

At the end of the class, everyone was exhausted. It’s a three hour class, but it felt longer. Some students were in deep conversations, unpacking a post-it note comment. Others slunk out quietly, their emotional reserve empty. Others joked boisterously.

All were changed. All came back to the next class more committed to each other.

As Danielle Forward wrote in her wonderful essay on getting feedback.

There’s a big difference between who we want to be — who we imagine we are — and what we actually are.

She goes on to say

It’s easy to tell yourself a narrative of who you are. We probably do it all the time. “I’m a good person, a good leader, and a good teammate,” but am I? Are you? How would you know? It’s this same skepticism, this same curiosity, that I think makes me a designer. That last week in class, I was the “product” — and I got to view the data about myself.

This is the true “gift” of feedback. To see yourself how others see you, and decide what to do with that information.

That’s all feedback is: information about how someone sees you.

I’m really glad I know that I’ve been coming across differently than I intend in group discussions. — Allesandro

But it wasn’t all kumbaya. One student was a bit wounded by the feedback he got, and I shared Chapter 10 from Thanks for the Feedback (marvelous book!) with the class. It’s about deciding which feedback to accept and which to discard. Learning that not all feedback has to be acted on may be the most valuable information I have ever gotten, and I was happy to share it out.

Is Feedback a Gift?

In the T-Groups I’ve done at Stanford, they always recite the mantra, “feedback is a gift.” It costs the giver something (you can make yourself vulnerable to rejection when providing feedback), and it provides the receiver with something (information you didn’t have before.)

I hate that phrase. Feedback never feels like a gift to me. Or rather, it feels like a gift with strings. When it’s negative, I feel like it comes with the demand, “change that.” When positive, I feel like it comes with “appreciate me for being so nice.” Or occasionally, “please reciprocate.”

I prefer another phase they use, “feedback is information.”

I like data. I like data a lot and I’ve worked with it most of my career. I know a single data point can be a clue to truth, or an outlier. A data point is worth exploring and gathering more. Feedback lets you do something you can’t any other way: see yourself through someone else’s eyes. Then you can adjust, moderate or amplify the behavior they see, depending on the results you want. It’s a lot like qualitative testing. It’s valuable if you are trying to understand why something is happening:

Why doesn’t that person want to work with me?

Why does that person look sad after I said that?

Why are my teammates so deferential around me?

Why do people interrupt me all the time?

Life is full of mysteries, and feedback can provide the clues you need to solve them. My students learned to give feedback, and to receive it. They have the tools to begin to understand how they are seen, and what behaviors hold them back. What they do with that data will be 100% up to them.