This one of a series of essays on speaking. Find more here.

When the Game Developer’s Conference invited me to give a talk on the User Experience of Games, I said yes faster than Jane Austin character to a marriage proposal on page 400.

I’ve been attending GDC for years because I love its entertaining blend of business, engineering and design. What could be better than to speak at my favorite conference?

Then I got a queasy feeling in my belly.

First, I got writer’s block. I’ll admit it, after twenty years of User Experience design I’m a bit over the topic. I spent months opening the PowerPoint, glaring at the handful of slides, and closing it again. Finally, a week before my talk, I had a flash of insight and sketched out a quick draft in post-its. The afternoon before the talk I reopened the deck, filled in the images, and closed it up.

Driving my daughter home from school, I got a flat. But the garage was right there, and they said my car would be ready in the morning.

Turns out “morning” is 10 am. My talk is at 12. I live a 45 minute drive away, so it should be fine.

Except there was an accident on the freeway.

And gridlock in the city.

I ran from the parking garage to the conference, dodging attendees who flooded the sidewalk, arriving exactly at 12, out of breath.

I’d driven rather than taken the train and walked so I wouldn’t arrive sweaty. Ha.

The conference technician mic’d me up, then said “Not sure we have an adapter for that computer.”

At this point I’d panicked and calmed down so many times that I wasn’t sure I had a panic left in me, “It’s just a mini displayport,” I said. My adapter was in a student’s pocket somewhere. Because it’s that kind of day.

“Ok,” he replied.

They rummaged in their adapter box while I eyed the packed room watching me. I had thought that maybe ten people would showed up. It looked like the room held 300.

Then I opened my presentation.

It was the wrong presentation.

It was my first draft. Not the final one I had polished the day before.

Gritting my teeth against a final wave of panic, I turned to the room volunteer and said, “I’ll start at 12:10 no matter what. Please tell the audience.” I tried to open up dropbox to find out what went wrong, but the conference connection was too slow. No time to dig through revisions. I went with what I had.

My talk was essentially PowerPoint karaoke. I looked at a slide, talked to it, tried my best to remember how I planned to relate each point to game design and moved on to the next one. Finally I saw the room volunteer hold up the five minute sign. By some miracle I was just finishing up. I took a couple questions, gave away some books, and said thank you.

I was mobbed at the stage with people asking questions afterwards, and we walked to the wrap-up room where I answered more questions and discussed strategies for good user experience for an hour. Finally, I made my excuses and slipped away.

As soon as I was alone, I texted my pal Erin, veteran GDC speaker.

“I need hugs.”

I was convinced I had just given the worst talk of my career. Erin insisted it went well. I thought she was just coddling me. But as I attended the rest of the conference, every day someone would come up to me and thank me for my talk. I slowly I realized I had done better than I thought.

Walking off the stage, I could only see the talk I planned to give and how far short I fell. But it turned out the audience thought it was good.

That’s all that matters.

Lessons Learned

I was able to survive that perfect storm for two reasons.

First, I know my material. I have over twenty years of speaking, writing and practicing User Experience Design under my belt. I could have had no slides and talked for 45 minutes. You know when teachers say, “write what you know?” It helps.

Second, perhaps more importantly, I had learned that speaking is performing. Performance is the presentation skill too few books talk about. Yet it’s the one skill that will save you when you are terrified and everything is fubar.

A few years ago, I got interested in being a better speaker. I wanted to hire a speaking coach, but they were all $350/hr and up. So I hired an acting coach instead for $125/hr. This was the best idea ever. Speaking happens on a stage, therefore it is a performance. And my coach knew performance.

You, On Stage

Kathy Sierra says about presenting, “You are the UI.”

“And what’s a key attribute of a good UI? It disappears.“

UI is a technical term meaning “User Interface.” It’s the part of the software program you see that lets you access the functionality of the software using buttons and tabs rather than typing lines like “ $ vi bar.txt”.

When a UI good, you don’t notice it, you just do your work. When it’s bad, you cuss a lot.

It’s the same for accessing the ideas in a presentation; the presenter gives access to the ideas in the talk without drawing attention to herself. You are not a circus entertainer, impressing people with your acrobatic feats. You should be unobtrusive, a conduit to stories and insights you are sharing.

But if you are monotone, or pacing back and forth, or saying um and er a lot, you are also making it hard for your audience to access your ideas.

Consider an actor in a play. How do actors prepare?

- They know their script.

- They block their moves.

- They rehearse.

- They use costumes and props.

- They treat their body as an instrument.

To Script or Not to Script?

I know people who script out every single word of their talks, then read it or memorize it. I am the kind of person who has a series of outlined points, and I know what I’m saying at each point, but I do not memorize the exact phrasing.

In highschool, I was what was called a “drama jock.” That means instead of sports, I hung out with the theater people. This was mostly the province of the extremely uncool until my senior year when a football player joined us. In Drama, we put on plays, as you might expect, but we also did drama competitions. Like basketball or football, you worked your way up from regionals to the all state competition.

The only time I made it to state was in improv. In improv, the judges give you three words, and you have to make a 20 minute skit out of them. My drama teacher taught me a method that was considered a bit controversial (perhaps illegal!) but it is perfectly good approach to improving your talks.

First you create your framing story. When I went to state, I had created a frame based loosely on “Get Smart” in which I was a secret agent trying to discover who was a double agent, then confront them. We’d battle, I’d win somehow and tada! The end. The great thing about this frame is no matter what peculiar object the judges gave me, from a cantaloupe to a fire hydrant, my secret agent contact could be disguised as it.

As I wrote about earlier, I design an architecture for my talks that acts much like an improv’s framing story. I then “decorate” that architecture with data, facts and insights. The biggest advantage to the architecture-decoration approach over a full script is that I can now reduce or expand my talk by adding or removing decorations. I can give a talk in 20 minutes, with fewer supporting examples and anecdotes, or in 45 or 90, by adding more. I can even do a half day or full day workshop by adding in exercises.

This also helps assure more accurate timing. I always have an ipad on stage with the clock maximized.

I know where I should be in my talk outline at each third of my time allotment (I like a three act structure.)

If I’m running fast, I can add in an anecdote. If I’m running slow, I can cut one. While it’s possible to be accurate in speech length with a memorized talk, I find sometimes I need to go slower because the audience is having a hard time following me (such as recent talks in Tel Aviv and Lausanne) and this flexibility in pacing is a huge asset.

Perhaps you’ve heard the advice to watch other talks at the conference you’re attending, and find ways to refer to them? This is easy with the improv-style frame.

Scripts

If you do choose to script your talk, treat it the way an actor treats a script. Actors start by reading scripts out loud to understand the material before they commit to memorization.

It’s critical to read it out loud. Columbia professor of linguistics John McWhorter talks about the difference between speaking and writing in his TED talk,

For example, imagine a passage from Edward Gibbon’s “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:”

“The whole engagement lasted above twelve hours, till the graduate retreat of the Persians was changed into a disorderly flight, of which the shameful example was given by the principal leaders and the Surenas himself.”

That’s beautiful, but let’s face it, nobody talks that way. Or at least, they shouldn’t if they’re interested in reproducing.

The written word is dense and tricky to read out loud. Writing has three-syllable words and semicolons. Speaking that way takes practice. To make sure you won’t be tongue tied when you are on stage, print out and read your entire script out loud multiple times.

First, go slowly, marking anywhere you trip or run out of breath. You can either change the script or practice until it goes smoothly.

Then read it again, adding emotion and emphasis. Record yourself. Check if you are reading in a monotone. See if you can bring some life to it. Pretend to be reading to a 8 year old kid. Then dial it back to a business setting. Your energy will be infectious. Be sure you bring passion to the topic, and your audience will respond with their own.

Next read it again and set a timer. How long is your speech when you read it at your best? Too long, too short, just right? Cut or expand as needed.

Now start memorizing. You may find you are halfway there from all your practicing.

The same practice schedule is fine for the improv-frame approach. You just don’t have a script to work from. Instead you have bullet points written on index cards.

Running short is my usual problem, but sometimes I do run long. I was at a conference in Europe, badly jetlagged and my talk started a few minutes later than scheduled. I’m a notorious fast talker, so I was shocked when I looked down at my ipad and realized I had five minutes left for fifteen minutes worth of material.

I simply dumped some anecdotes, didn’t take any questions and I wrapped only a few minutes after my scheduled finish time.

Life surprises us. It’s good to have a plan B.

Beginnings and Endings

No matter if you’re an improvist or a scriptor, there are two things you really really want to script and memorize:

- Your beginning. I wish I had a penny for every time a speaker took the stage and looked around and then said, “Ok, well, thanks, I appreciate being here, hey…” I also wish some of those pennies weren’t for me.

One of the single best things I’ve learn to do is carefully write out my first few lines and memorize them. That way when you step on stage, heart pounding, audience twice as big and twice as cranky as you expected, the words flow out of you. - The Ending. You need to plan for exactly what you say at the end of a talk, or you’ll be saying “and, that’s it. the end I guess. Thanks for coming.” UGH!

Instead, decide if you want to end with a joke, a call to action, or a request for money. Hey, no shame in telling people you are for hire, if that’s why you’re on stage!

The first and last lines are what people will remember. Make them count!

Using Notes

In Chris Anderson’s new TED book, he reveals how his thinking about how a TED talk should be made has evolved. Originally he started very formulaically. He believed that you should write a script, memorize it, practice it, then perform it. But as he worked with accomplished performers who had their own style, and accomplished thinkers who had no style and fell apart trying to adapt to the “TED way,” he realized that it was more important for a speaker to be comfortable.

Anderson shares the story of the Nobel laureate, Daniel Kahneman:

“ He hadn’t been able to fully memorize the talk and so kept pausing and glancing down awkwardly to catch himself up. Finally I said to him, “Danny, you’ve given thousands of talks in your time. How are you most comfortable speaking?”

He said he liked to put his computer on a lectern so that he could refer to his notes more readily. We tried that, and he relaxed immediately. But he was also looking down at the screen a little too much.

The deal we struck was to give him the lectern in return for looking out at the audience as much as he could. And that’s exactly what he did. His excellent talk did not come across as a recited or read speech at all. It felt connected. And he said everything he wanted to say, with no awkwardness.”

― Chris J. Anderson, TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking

You have to find a speaking style that you are comfortable with. But that does NOT give you licence to keep reading off your slides as you always have. If you’re looking down, you aren’t connecting.

So what can you do, if you don’t have time to memorize or don’t want to? Higher-end conference often offer confidence monitors, so you can see your notes as you speak. But what if the conference doesn’t have it?

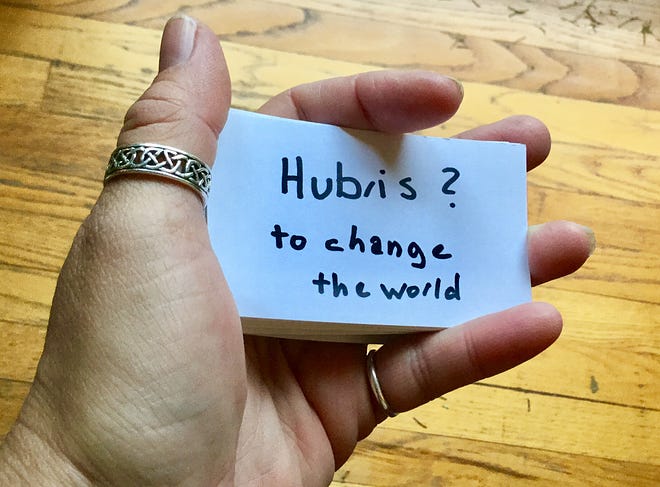

Try good old fashioned index cards. It’s what your high school teacher advised, right?

I actually prefer blank flashcards. they fit nicely in the palm of your hand, so they aren’t obtrusive, and can hold one talking point prompt.

I actually prefer blank flashcards. they fit nicely in the palm of your hand, so they aren’t obtrusive, and can hold one talking point prompt.The key is to remember to put the top one under the stack as soon as you see it. The first time I used this technique, I forgot to, and then they were useless. How embarrassing would it be to have to say, “Hold on a sec while I find my spot!” You’re better off winging the rest of it. After all, you practiced?

Right?

Once More with Emotion

Rehearse, rehearse, rehearse, but not just to memorize. Pick your places to pause. Note them in your deck and/or on your notecards. Vary how you speak. Where will you slow down? Speed up? Should you sound sad? wry? Resigned? Bemused?

Nothing is more boring than listening to someone drone on in a monotone. Don’t be that person!

“rehearsing the transitions is especially important. The audience needs to hear in your voice when you’re doubling down on an idea, versus when you’re changing subjects.”

― Chris J. Anderson, TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking

Now let’s talk about how we’ll rock the stage….